On April 11, 1997, two hours before the first tee time for the second round of the Masters, Linda Caldwell walked onto the back porch of her home in Martinez, GA., three miles from Augusta.

Immediately she saw her husband, Allen, slumped in a chair, wearing his maroon and white robe. A 12-gauge Remington was wedged between his legs, and a pool of blood gathered on the deck.

Shortly after local police began their investigation, it became clear to them why Caldwell took his own life: He couldn’t secure the hundreds of Masters badges that he had sold to corporate clients descending on Augusta.

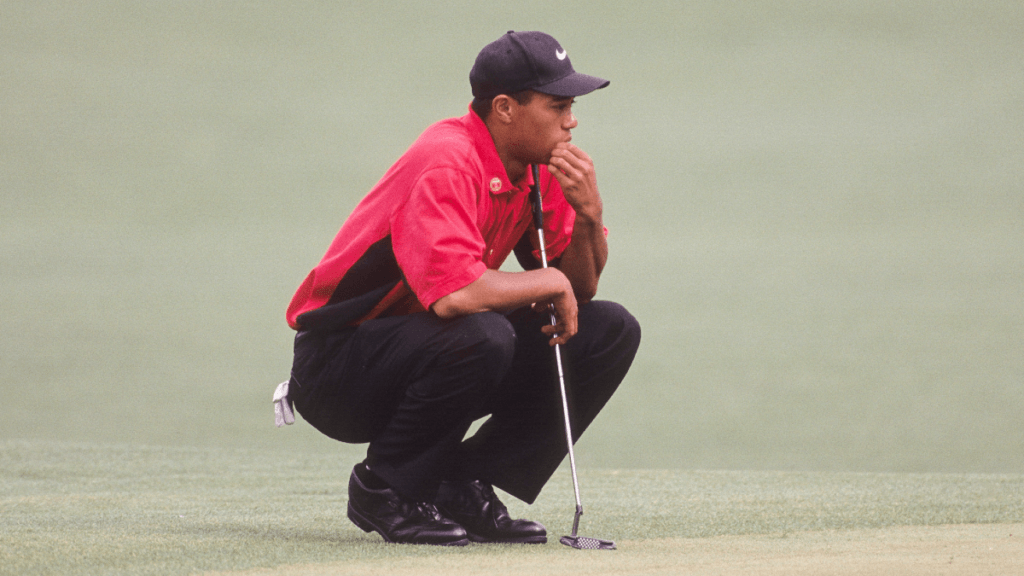

Tiger Woods' remarkable first major win at the 1997 Masters, 25 years ago this week, is a story that is told over and over again. The 21-year-old smashed Augusta National records, winning by 12 strokes and searing the Sunday red shirt and the fist pump into our minds forever. But the detailed story of the ticket market created around Tiger and the man who died because of it, has remained a relative secret — until now.

Twenty five years later, we traced what happened to the marketplace for badges, how it became the hottest ticket in sports history, and how it affected Allen Caldwell. We talked to those close to Caldwell, most of whom didn't want to be quoted, and reviewed the investigation by the Columbia County Sheriff’s Office.

Allen Caldwell was the owner of a liquor store, M&C Spirits in Martinez. Through the liquor store connection, Caldwell befriended people in the community, including members at Augusta National. And that helped him recognize an opportunity.

Augusta National members have the right to buy badges, which give its holder access to the entire four-day tournament. These badges are mostly only available to members; the club has not offered them to the public since 1972. Patrons are discouraged from selling them, the total of which is a guarded secret. The club numbers and color codes each badge to correspond with the name of the member they were assigned.

But the delta between how much members are asked to pay versus how much the badgers are worth on the open market is a tempting opportunity.

From 1993 to 1996, each badge cost $100. Members would then quietly sell them to a trusty middle man like Caldwell, usually for $400-$450 a round ($1,600 to $1,800 in total). Over several years, Caldwell built a nice business bundling the badges into a hospitality package that included a rental home.

Leading up to the 1997 Masters, Allen Caldwell entered into a partnership with a company called World Golf Hospitality, which had a much bigger corporate client list than Caldwell could wrangle. To increase the value of his package, Caldwell purchased a dilapidated bar on Washington Street across from Augusta National's Magnolia Lane entrance and converted it into a hospitality suite. Caldwell and World Golf Hospitality sold tables to the newly named The Clubhouse to corporations for $22,000 to $25,000 apiece for the week. The tables came with food, drink and, of course, badges. Big companies and brands like Absolut Vodka, Texas Instruments and New York banks like Morgan Stanley and Lehman Brothers bought in big.

Caldwell didn't sign any contracts with the members who said they'd sell him their badges. Augusta National stipulated that members could not sell their badges and if they were found to have done so, they could have their membership privileges stripped. But Caldwell did have a list of names and knew where he needed to go to get the badges when it came time.

Investigation records show that World Golf Hospitality paid Caldwell $440,000 to secure the badges. The investigation found that World Golf’s deal with Caldwell accounted for badges to be bought for as much as $1,800, meaning that if all of them cost him that much, he’d still acquire nearly 250 badges for four days.

Then came Tiger Woods.

Woods had participated in 17 PGA Tour events as a professional at that point. And the world was starting to figure out just how good this kid was. He finished in the top 5 in seven of those tournaments, winning three. Masters badge buying is very much a “month before” activity. As the tournament drew closer, and the buzz around Tiger grew, the market for badges intensified. Suddenly, a few weeks before the tournament, the asking price for a badge went from $1,500 for the four-day tournament to $3,000.

Then, 24 hours before The Masters began, the market exploded. That’s the day Phil Knight — the man who dared to pay Tiger $40 million for five years to endorse Nike — came into town with a slew of company executives. The word on the street was that they would do what it took to secure badges. By Wednesday afternoon, badges were going for $10,000, the most expensive ticket in sports history.

At the Augusta National entrance on Washington Street, one broker was screaming the price he was willing to pay.

"Eight thousand dollars," he yelled. "Eight thousand dollars a badge."

"The craziest part about it was that no one even looked at the guy," said another broker who was there. "It was like, even that dollar figure, no one was considering selling."

Caldwell realized he was in trouble.

Historically, the price of badges had dropped as the tournament grew near. So much planning would go into corporate America flying in that the last-minute market was only ripe for a local like Caldwell, who knew what he was doing.

Believing that trend would continue, and unbeknownst to his business partners, Caldwell sold a lot of the badges to secure a healthy profit for himself when he thought the market was at its peak.

Suddenly, thanks to Tiger and Nike, prices skyrocketed.

"Masters badges were like winning the lottery to Allen," said Austin Rhodes, a local radio broadcaster who talked to Caldwell every day that week on the air. "It was going to be a life changing experience. But once things turned left, Lord have mercy did it get bad."

On Thursday morning, as folks started to arrive at The Clubhouse, this much was clear: Allen Caldwell no longer had the Masters badges he promised — and no longer had a way of getting them.

Morgan Stanley, which was expecting 40 badges, couldn't disappoint its bankers and their clients. So it made as many calls as possible, and just like Nike and Phil Knight, said that money was no object. A few hours later, the bank had purchased 40 badges at what sources say worked out to about $14,000 each.

On Thursday afternoon, realizing their fate, Caldwell and his partners held a meeting to talk about what to do. Caldwell revealed that he had the money he made from initially selling the badges and that the business could go on, at a smaller scale, if they could secure some badges. That was the plan when they broke off Thursday afternoon.

"We were pretty much going to do the best with what we had and everyone was on the same page," said a source privy to the conversation.

It's why his partners were shocked when they found out that Caldwell had killed himself the next morning.

"We had enough money to buy badges so that we could get people to be at the course for a day here and a day there," said a person close to Caldwell.

But the embarrassment of not being able to deliver to all, knowing the miscalculations he had made, was said by investigators to be a lingering factor.

Augusta National, whose executives, current and former, still won't talk about what happened to Allen Caldwell. Attempts to contact current Augusta National executives were not successful. Former spokesman Glenn Greenspan declined to comment.

It's not known exactly how much Caldwell and his partner World Golf Hospitality owed those who didn't get their badges, but sources say most of them received their money back.

As for Caldwell, the build up to what became the craziest hot-ticket market in sports history hurt his ability to deliver on the Masters business he dreamed of building. Facing a tarnished dream, he ended his life, leaving behind his wife Linda and young son.

Although The Clubhouse didn't come back, Linda's stake in the enterprise was purchased by World Golf Hospitality in what is believed to be a settlement of sorts, a lawyer disclosed in 1998 and confirmed by Action Network. Linda declined to comment for this story.

"He had experienced financial, personal and professional disaster in a relatively short span of time," wrote investigator Harold Clack, in the official file that has since been destroyed. "And the situation apparently seemed hopeless and he was helpless to turn the tide of events. Case Closed."