Strategically, Germany are the most refined team at the Euros, and that is why they are the most likely to win the competition.

When Die Mannschaft sacked Hansi Flick and appointed Julian Nagelsmann in his place last September, the tactics community immediately took notice. Given Nagelsmann's track record with developing and detailing squads at Hoffeinheim, Leipzig and Bayern Munich, it was clear he'd do the same for Germany.

Whether that would be enough to push them into the echelon of true contenders — especially after they've fallen well short of expectations at three-straight international tournaments — was still in doubt. France and England, while less advanced strategically, both have more attacking firepower and, at the very minimum, can go toe-to-toe with Germany in most other positions talent-wise.

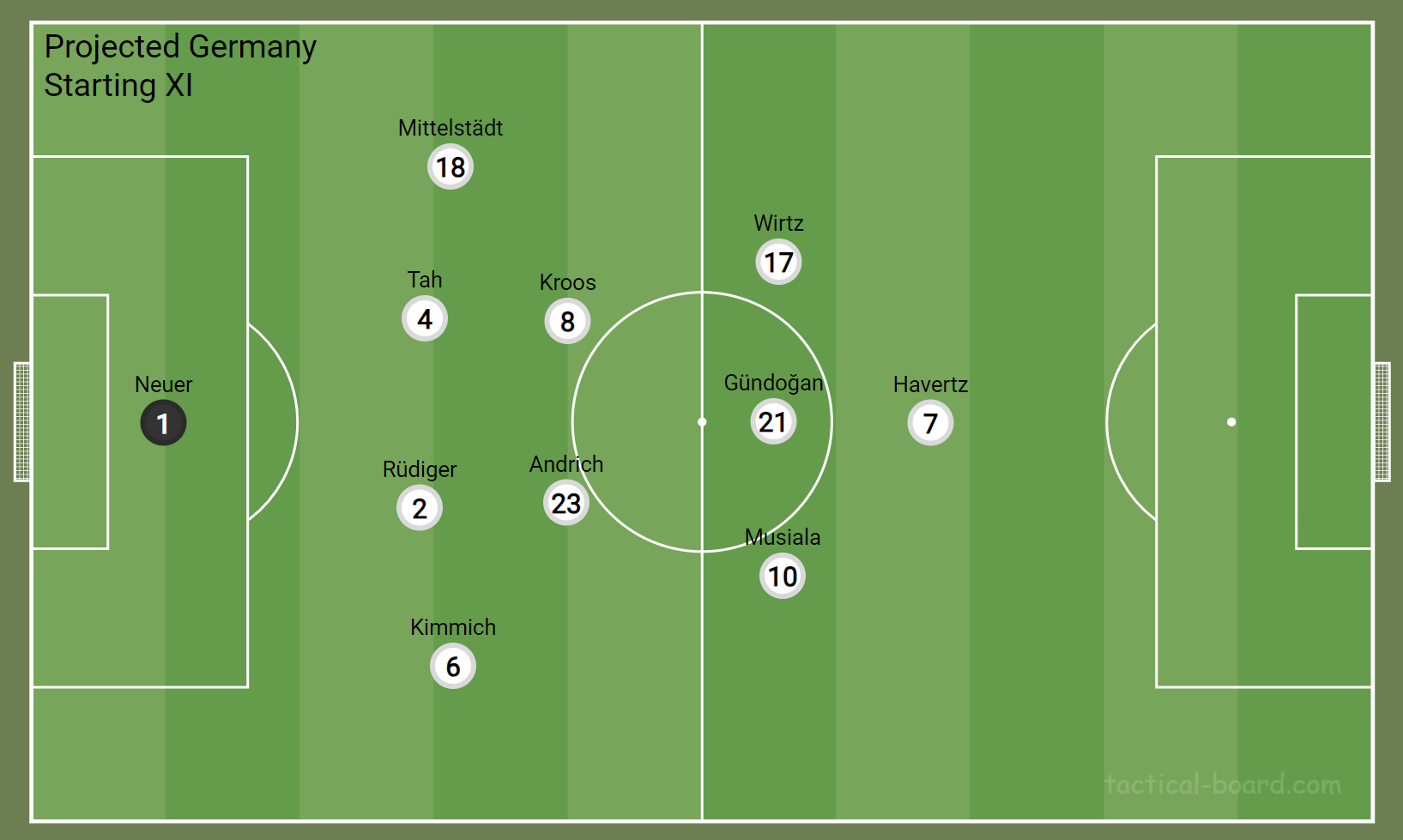

That was until Toni Kroos announced his return to the national team in late February. All of the sudden, Nagelsmann didn't have to shoehorn profiles into the midfield that didn't belong, as he now had a world class option in that area of the pitch. Joshua Kimmich could move to right back, where he is more comfortable, İlkay Gündoğan could be deployed further up the pitch and Leon Goretzka (rightfully) stopped getting called up altogether.

All of the knock-on effects from Kroos' return fit into the larger pattern of Nagelsmann shaping his squad from the available talent pool much more effectively, and then correctly profiling the players he called up. Robert Andrich and Maximilian Mittelstädt are perhaps the two best examples of this, having both made their senior international debuts under Nagelsmann, and appearing to be first-choice in roles that suit their skillsets. In short, Nagelsmann is already well on the path of maximizing what he has available to him just by doing something simple – playing the right players in the right positions.

However, proper profiling is only part of the battle of building a side that can compete with France and England, and this article is here to explain the rest of what Nagelsmann has done to make them a serious contender. It'll be broken down into distinct sections for each of the four phases of play — in possession, out of possession and the transitions between them. While I'll do my best to partition those segments into smaller parts, soccer isn't always easily divided into distinct situations, so be prepared for some overlap (not just from Germany's fullbacks, I will add).

One last note. To be transparent, I watched both of Germany's matches — a 2-0 win against France and a 2-1 victory versus the Netherlands — from the March international break to research this article.

Germany Out of Possession

Since soccer is a cyclical process, every team's decisions in one phase of play influence what happens in the other phases. While there's no natural starting point, as you watch a side, a beginning that makes sense tends to emerge.

With Die Mannschaft, that launchpad is their out-of-possession approach. When opposing teams try to play out from goal kicks and similar territorial situations, Germany will employ a "hybrid" press. As the name suggests, a hybrid approach mixes man and zonal responsibilities to get the best of both worlds.

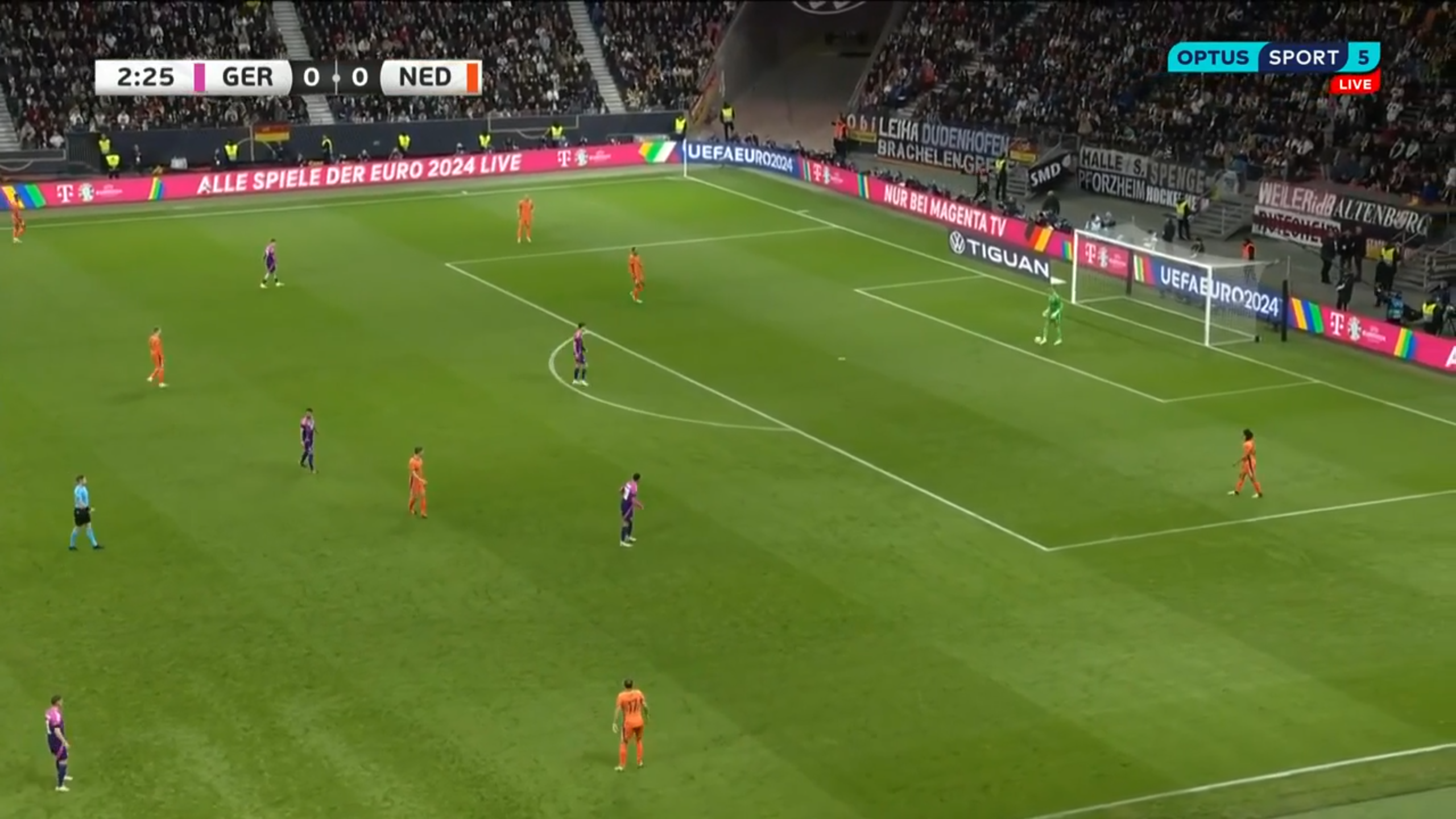

Here's an example from the opening moments of the Netherlands match. Germany starts in a zonal arrangement, with their front four responsible for six opposing players (including Bart Verbruggen in goal) and the rest of their team man-aligned, as is evident by Kimmich pushing up in response to Daley Blind's deep positioning as a left wingback.

Verbruggen's first pass to Nathan Aké triggers the man-to-man press. Jamal Musiala jumps to Aké, Kai Havertz steps forward to discourage the Dutch center back from playing back to where he received the ball from, Andrich pushes onto one half of the Netherlands double pivot while Gündoğan gets tight to the other half and Kimmich works to close the distance between him and Blind, who droppped even further toward the ball.

Aké is forced to open up and force a ball forward, around Musiala's pressing run, and when it doesn't come off Germany can easily recover possession.

Hybrid pressing approaches do require an intelligent group of players to pull off, as their on-pitch awareness and ability to process and quickly respond to any adjustments made by the opponents is paramount. Across the board, Germany do have that, but they aren't immune to mistakes.

Just moments later, Netherlands find themselves in a similar, but slightly different situation to the one described above. Matthijs de Ligt has the ball on the edge of his own box and Verbruggen is behind his back line, instead of stepping in like he did earlier. Germany's structure is nearly identical, with the front four in the same 3-1 zonal shape as before, the fullbacks pushing up onto the Dutch wingbacks and Andrich in a zonal midfield role, but ready to jump to Joey Veerman as he did previously.

There is one crucial difference, though, and that's how Germany responds to the movement of the Dutch front three in this 3-4-3 build-up shape. Tijjani Reijnders, playing on the right of this narrow front line, drifted toward the touchline, which Toni Kroos followed, as Mittelstädt had pushed so far forward from left back.

That leaves a massive pocket of space next to Andrich, so Memphis Depay just drops into that area, between the cover-shadows of Gündoğan and Florian Wirtz, and neither center back follows. He's demanding the ball in the image, and de Ligt eventually recognizes and plays that pass, which puts Depay in a situation to turn and run at the German back line.

Germany rarely commit these sort of errors — and adjust quickly when they do. However, in a knockout match, one mistake is sometimes all it takes, so it's important to recognize the risks that come with this defensive approach.

Now, even though they are a ball and territory-dominant team (as will be discussed later), Germany won't be in high-press mode in every out-of-possession situation. Usually, they'll be positioned in their mid/high block, with the ultimate aim of winning the ball back, but not as immediately aggressive in achieving that.

Die Mannschaft are flexible with their shape in this phase of the game, and they adapt as necessary depending on how their opponents line up. France deployed a pretty vanilla 4-1-2-3 against them, with Aurélien Tchouaméni as the single pivot. In response, Germany went with a 4-2-4 block structure, with Gündoğan and Havertz as the two strikers and very snug, blocking access to Tchouaméni.

In their clash with the Netherlands, a team that used a 3-4-3 with a double pivot, Nagelsmann elected to deploy a 4-2-3-1, with Gündoğan in the middle of the line of three behind Havertz. There are some quirks with the in-possession play of the Dutch that influenced some small details of Germany's defensive plan here, but as this is not a Netherlands breakdown, they're unimportant.

What is important are some of the characteristics of Germany's mid/high block that are in play no matter the arrangement of the 10 outfield players on the pitch. First, notice Germany's compactness — there's never more than 10 yards, usually closer to five, between lines, and horizontally they are incredibly tight. This is most obvious with their front four in the 4-2-4, with Wirtz and Musiala extremely narrow, blocking the half-spaces.

Additionally, the German fullbacks are in-tune with the heights of the opposing width-holders. Against France, Kylian Mbappé and Ousmane Dembélé are high and wide, so Germany are in a standard, flat back four. The Netherlands, however, had basically no one high and wide, so Kimmich and Mittelstädt are narrow and step a few yards forward relative to the center backs.

With such an emphasis on limiting central access, Germany's obvious weakness is in the wide areas. They'll usually try to engage their press, squeezing opponents to the touchline when the ball goes wide, but as you can see in that setup against France, the distance between the German wingers to the French fullbacks is extremely large.

That can be exploited via circulation in the back line, particularly by working the ball slightly to one side before quickly reversing it the other way so the fullback has enough time to make a positive attacking decision with the ball. France's in-possession strategy was incredibly poor, but in the moments they were able to get Lucas Hernández and Mbappé combining down the left they were extremely threatening.

One other solution to this Germany 4-2-4 block is to utilize the goalkeeper as a +1. Here, Brice Samba steps into the back line, with the rest of the back line spreading out. This puts the two German strikers in a bind, as they have to respond to both the width of the French central defenders and the possibility of a ball from Samba to Tchouaméni. It's an unsolvable problem for them, and it isn't helped by the fact their wingers have to respect the positioning of the French fullbacks, who are hugging the touchline.

Havertz and Gündoğan stay narrow, and that leaves a lane between Havertz and Wirtz from Benjamin Pavard to Randal Kolo Muani at striker, so Samba gives Pavard the ball.

Kolo Muani abandons the last line well to wall-pass the ball to the now-free Dayot Upamecano at left center back. From here, there's space wide left for Hernández and Mbappé to once again combine.

Because of Germany's high line of engagement, preferring to defend in their opponent's half, they hardly ever end up in a low block, defending their box. Opponents will try to exploit the transitional moments that arise when they get through the press or high block, which comes at the expense of ball retention, so they hardly ever have settled possession that far forward. When they are deep, Die Mannschaft go with a 4-2-3-1 shape, but it will happen so infrequently that it's really not that important.

Ultimately, no defensive structure is going to be perfect or lacking any weakness, but this Germany team gets pretty close with excellent defensive principles at both the macro and micro levels.

Attacking Transitions

Germany's attitude toward the subsequent actions after winning the ball back is highly contingent on the situation, because their defensive approach produces a variety of scenarios where possession is turned over.

After any high turnovers caused by their press — or even counter-press, as will be discussed later — they will try to exploit that moment of chaos with forward runs off the ball and quickly verticalizing play. This isn't a regular occurrence though, as most teams won't try to play through Germany's press.

When they win the ball back deeper, Germany are much more reluctant to immediately push forward. This is especially true when they have numerical inferiority against the players back defending for the opposition. Instead, they will recognize those unfavorable conditions and play a couple of quick, short passes to reestablish control. This discourages the opponents from counter-pressing and also gives their own players time to organize themselves into their attacking structure.

It's also worth pointing out this Germany lineup, as is, is not that suited to counterattacking play. Yes, every player is better when they have more space, as transitions afford them, but a lot of these guys are "special" because of what they can produce in tight corridors against a settled block. Wirtz's ability to find pockets in a defensive shape and arrive in them, Musiala's dribbling under extreme pressure and Gündoğan's knack for ghosting into the right spots in the box are all examples of this.

However, Nagelsmann does not lack the profiles in the squad to make his team more potent when transitioning from their deep block. In game states where they're focused on protecting a lead and are less ball- and territory-dominant as a result, wingers Leroy Sané and Chris Führich are perfect options off the bench. Both have the ball-carrying and running power to drive up the pitch on their own and maximize the spaces that open up when a team is chasing a goal.

Germany In Possession

While Germany are incredibly stable against the ball, it's when they have possession that they truly shine. There's just something beautiful about a side with elite technical quality across the pitch that wants to display it at every possible moment, and there isn't a team in this tournament that describes better than Die Mannschaft. Be prepared for a lot of praise this section, but I promise you it's warranted.

First off, it's unlikely Germany are going to face many high presses in even or losing game states due to their sheer on-ball ability and collective problem-solving capacity. However, when they do come across them, they are capable of playing through them. It starts with Manuel Neuer, still one of the best goalkeepers with the ball at his feet out there, who not just joins the build-up as a +1, but also knows how to join it. He will pick the right passes and provide the right angles for his teammates.

Then there's Kroos. The Real Madrid midfielder has been singlehandedly conjuring up solutions to opposing presses at the club level for a decade, and he'll function as a get-out-of-jail-free card in his last hurrah with the national team as well. This is down to two factors: his information gathering and processing and ability to disguise his intentions. He simply knows where the next pass should go, and he can deliver that ball in such a way that gives the the receiver advantageous body orientation plus time and space.

Here's an example from the France match. Down two goals, Les Bleus have been almost forced to start pressing high if they want to get back into the match. Against what was roughly a 4-2-4 from Germany — Gündoğan begins deeper here, so it looks like a 4-2-1-3 to start — France engaged in a man-to-man 4-1-4-1.

Kroos drifts into a position between Jonathan Tah and Mittelstädt to receive from Tah. In response, Warren Zaïre-Emery jumps to Kroos while Adrien Rabiot follows Andrich.

Kroos then turns to his left and finds Mittelstädt, who is faced with immediate pressure from Dembélé. France are in a very good position here, with basically all possible options covered. However, there's still the man in white wearing No. 8 to worry about.

After playing to Mittelstädt, Kroos drops back 10 yards and widens a bit to provide an angle for the left back to play back to him, which is exactly what Mittelstädt does. As Kroos turns his body to seemingly play back to March-André ter Stegen in goal, Zaïre-Emery jumps again and Kolo Muani starts cheating with his position in anticipation of closing down the goalkeeper. However, Kroos' true desire was to play across his body to Tah, who is now free because of Kolo Muani's response to Kroos' body orientation.

This is a concept referred to as "torso deception," and a lot of players use it to disguise their intentions with the ball. Very few, if any, are better than Kroos in this regard, and it's part of the reason why he's such a headache for opponents.

Tah, thanks to the placement on the pass from Kroos, now has space to drive forward, forcing France back. So much of soccer is about finding the free man facing forward, and that's exactly what happens here.

From there, the movement of Germany's front four causes the man-marking of France's back line a ton of problems, so when Tah plays across to Andrich, there's an easy ball to Kimmich completely free on the right wing.

This sequence not just displays the quality and inventiveness of Germany's build-up play, but also how they look to exploit "faux transitions" when they arise. Generally, a "faux transition" refers to a moment that's like a turnover with regard to the immediate numerical and dynamic advantage afforded to the team with the ball, but doesn't arise through a change in possession. Usually, that happens when a side breaks the press of an opponent and generates forward momentum against a disorganized back line.

Like their actual transition play, Germany won't always force the faux transition from deep if the conditions aren't ideal. Most of the time, they prefer to incrementally progress the ball to around the halfway line and then manipulate the opposing team's mid block from there.

In this area of the pitch, which is referred to as the "second phase," Die Mannschaft get into the 3-1-6 structure laid out above. The 3+1 is incredibly fluid and the distances stay tight, which helps with retention and the counter-press (as will be covered later). Sometimes Kroos shuttles into a left center back position, leaving Andrich as the single pivot, and other times Andrich drops between Antonio Rüdiger and Tah and Kroos stays ahead.

Regardless of the arrangement, it was very quickly apparent how instrumental Kroos is in Germany's in-possession play. He's the team's metronome and the conductor of everything, and if there were any other musical terms that could be used to describe him, you can bet they would be in here.

What's perhaps most impressive about this version of Die Mannschaft is their ability to find solutions depending on the setup of the opposing mid block. It's abundantly clear how Nagelsmann has armed these players with a variety of ideas, and it doesn't take them long to figure out which tool in the toolbox is needed to break down the opponent's defense.

Against France, it was the combination of two things. Les Bleus basically left Kolo Muani on his own against Germany's 3+1 in a 4-5-1 mid block. With Zaïre-Emery and Rabiot pinned deep by Wirtz and Musiala and their wingers having to respect the width and height of Germany's full backs, there were massive pockets of space behind Kolo Muani in front of France's midfield line.

Through a multitude of patterns, Germany were reliably able to find Andrich in that position.

In this sequence, Tchouaméni scrambles to attempt to close down the Leverkusen midfielder, but he has far too much time and fires a pass into Gündoğan in the lane between the French defensive midfielder and Rabiot.

In the Netherlands game, they faced a completely different proposition, but sill had answers. The Dutch team deployed a 5-3-2 mid block, but the near-side wingback would push up onto the German fullback. Reijnders, on the right of the midfield three, was basically man-marking Kroos. Those facets of their block, along with the poor engagement of the wide center backs on Germany's half-space occupants, opened up pockets on both sides of their double pivot.

Because of Reijnders' jumps to Kroos, even when he wasn't getting the ball, the Dutch double pivot had to cover a lot of ground laterally when Germany circulated the ball around the back. Here, Rüdiger plays across to Tah, which leads to Memphis Depay closing Tah down and Reijnders pushing out to Kroos.

Gündoğan sees this unfolding in front of him and recognizes the lane that's about to open, so he arrives in the space vacated by Reijnders, with neither de Ligt or Jerdy Schouten able to get close to him. Tah drives the ball into his path.

The Barcelona midfielder plays a one-two with Andrich to readjust his orientation to the right side of the pitch, and with the Dutch double pivot having to shift so far to Germany's left previously, there's now a massive pocket of space on the right. Additionally, with de Ligt having jumped out of the back line, Aké and Blind are now man-to-man with Havertz and Musiala, which is bad for two reasons.

First, Kimmich is just completely free because Blind has had to abandon that assignment to not leave Musiala completely on his own. Second, man-to-man engagement in the last line in a situation like this is super manipulable with well-timed movements. Havertz moves toward the ball, dragging Aké with, while Musiala runs in behind into that vacated channel.

Gündoğan elects to find Kimmich, who can carry into space. Additionally, Wirtz recognizes an opportunity as soon as that pass is played and starts to make a run across the face of Virgil van Dijk.

Kimmich plays a ball for Wirtz, who has a step on van Dijk, to latch onto. Now Germany has entered the final third with momentum as a unit and with numbers flooding into the box.

Wirtz turns around and finds a square ball to Musiala, but he slips after opening up his body to try to bend a shot inside the far post. Also note the movement and positioning of the German full backs here. Kimmich is providing an underlap, and Mittelstädt has narrowed far-side.

The end of this sequence introduces a key principle of Germany's second phase play, which is the complementary movements of the front four. This is known as "push/pull dynamics," which describes exactly what Havertz and Musiala did — one player abandons the last line while another makes a run in behind, into the channel covered by the defender of the first player. If we're being picky, Gündoğan should've played a ball over the top to Musiala, who had space and a step on Blind, to maximize that situation.

This was, unsurprisingly, a big feature of their progression play against France as well, including in the lead-up to their second goal. After Wirtz was able to cut inside, across Jules Koundé at right back, a similar pattern emerges. Havertz moves toward the ball, dragging Upamecano with, and Musiala makes a run into the space behind Upamecano with inside leverage on Hernández (to borrow a term from the other football).

Wirtz eventually played the ball to Musiala, who took the ball around an on-rushing Samba and cut it back for Havertz to fire into the net from about six yards out. Germany will play balls over the top when it's suitable to do so, and they certainly are not a team that has to play every pass on the ground, in front of the opponents' back line.

After overviewing the jobs of the "back" four and front four, that just leaves the full backs. Primarily, they're there to provide width, although depending on the other team's defensive structure, their heights can change. For example, against the Netherlands, who were aggressive with jumps from their strikers on the German center backs, Kimmich stayed deeper to provide a lateral support option for Rüdiger like Tah had with Kroos. Kimmich is proficient at delaying his actions and readjusting his angles to escape pressure when he receives wide, and he did that a lot in that match.

Combined with the narrowness of Germany's front four, they can also use their height to pin the opposing wingers, like they did against France. Mbappé and Dembélé couldn't narrow too much (to block the half-spaces) or push up onto Germany's first line without leaving easy access to Kimmich and Mittelstädt.

Additionally, there will sometimes be interchanges between the fullbacks and wingers later in a sequence of attacking play. While the usual space occupation (wingers narrow, fullbacks wide) is more favorable, these rotations can serve a purpose given the profiles of Kimmich and Mittelstädt. Kimmich is an adept creator in the right half-space, and Mittelstädt's ball-striking on his left can be used to great effect in more central areas.

Here's an example where the way a sequence has led to rotations and Kimmich getting on the ball in the right half-space. Additionally, it shows the principle of minimum width, where the far-side width-holder won't go all the way out to the touchline. In this situation, this gives Mittelstädt the possibility of making a run into that wide space, or also getting the ball in a narrower position, which is what happens. He makes a good blindside run into the lane Kimmich is oriented toward, and he ends up putting a shot on target after receiving in stride.

A lot of Germany's final third principles have already been covered, because most of what they do in the second phase carries over in more advanced positions. On top of that, some of the examples for their second phase play have just introduced what happens in the attacking third. To recap, Germany like to arrive in this area as a unit and attack it immediately. That happens by flooding numbers into the box, wide players receiving support runs (usually underlaps) and that 3+1 rest defense pushes super far forward.

Defensive Transitions

When Die Mannschaft lose the ball, it's all about the gegenpress, or in English, counter-press. This is enabled partly by their restverteidigung, rest defense, which maintains short distances and stays in contact with the front line, even when they push into the opposing 18-yard box. Much of soccer is about preparing to lose the ball when you have it, which sounds paradoxical, but it is true. If a team doesn't stretch itself out with the ball and try to play difficult passes, they will naturally have easier transitional situations to defend against.

This sequence from the Netherlands match not only gives an example of Germany's transition defense, but sums up their ethos nicely, so it seems like a fitting way to finish off the tactical analysis. Netherlands are in their typical mid block setup, with Dumfries as the near-side wingback pushed up and Reijnders sticking to Kroos like glue.

Prior to the still image, the ball had circulated from right to left, with Wirtz arriving on the right of the Dutch double pivot to receive from Tah. The German left winger immediately set the ball back for Tah and then made a run into the space de Ligt had vacated by following, but not wanting to leave a local option free, Schouten jumped to Andrich. That meant Veerman had to come across to not leave a massive gap for Gündoğan to receive in.

As was previously mentioned, a shift in that direction means space opens up on the other side. However, both Donyell Malen and Veerman are alert to this, so when Tah plays back across to Rüdiger, Musiala isn't an option.

Schouten still has to return to his position, and seeing a lane emerge to Gündoğan sitting between the two Dutch pivots, Rüdiger tries to fizz a ball into his feet.

Rüdiger doesn't disguise the action well enough, and before he's even struck the ball Schouten has started sprinting to cover the gap and is able to intercept as Gündoğan tries to receive and turn.

Now, this is where Germany are Germany. If Schouten's anticipation is impressive, this counter-press is even better, particularly Kroos' reading of the situation. Schouten immediately lays the ball off to Veerman, and before he plays the pass, Kroos is already in a full sprint closing down Reijnders after recognizing the turnover and responding swiftly.

Reijnders tries to turn, but is immediately met by Germany's midfield general, who wins the ball back. This is enabled by the short distance Kroos had to cover, but also because his brain worked so quickly that he was able to close that gap in a flash.

Conclusion: Germany +550 to Win the Euros

It's no surprise a national team with one of the best coaches in the world looks as good as Germany do in all phases of play. Putting Kroos into the midfield has added another dimension to an already well-drilled side, and as a result they are my favorites to win the Euros.

This is a team that will find ways to cause problems to whoever they face, and in a pinch they still have the player quality to fall back on. Given how far ahead they are of everyone else at the tournament tactics-wise, Die Mannschaft have been severely mis-valued to only have the third-highest odds (+550 via bet365), behind France and England, to win the competition. On top of that, they're at home looking to make up for three successive failures in major international competitions. Until that number gets close to +200, which it likely never will, they've been undervalued massively.