As I was flying home from a red-eye flight from Israel, where I had spent the summer of 1994, I could not believe the baseball season was going to end prematurely.

I had understood the basics of collective bargaining and the idea that the only way the players union could pry more out of the owners was to stop the season dead in its tracks.

But as a 16-year-old who truly loved the game, I couldn't imagine playing through mid-August and then just calling it off.

Then, it happened: On Aug. 12, the league shut down.

And when things came back for Spring Training, I was gone. Gone from baseball forever.

Only to come back here and there for occasional games, but never to my true self — not even back to a shell of the kid who spent the summer of 1991 trying to memorize the Baseball Encyclopedia; the kid who drained the ink on the fax machine in his father's office, slinging around weekly stat updates as commissioner of The Bo Diaz Memorial Rotisserie League.

True, timing wasn't kind.

I was a fan of the New York Mets, who won the 1986 World Series. My favorite player, Gary Carter, had gone to the West Coast in 1990 to play for the San Francisco Giants and the Los Angeles Dodgers.

My second favorite player, Darryl Strawberry, joined him. And my favorite pitcher, Dwight Gooden, was suspended for the 1995 season for using drugs.

When the season opened in '95, I had mostly checked out, subsequently hitching my fandom like never before to college football and the NFL.

The university I was going to attend, Northwestern — which had a woeful history in football — miraculously made the Rose Bowl, and it was all over. I no longer had time for the rawhide.

When some of the masses came back, thanks to the Home Run Chase of 1998, I thought it was cool. But that was all.

I say all this because I left 25 years ago, and it was much harder to leave 25 years ago than it is today.

The things that sucked me in — The Sporting News, Baseball Weekly, newspaper box scores — aren't in front of your face like they were.

Baseball is more avoidable than ever before. You don't have to watch tons of highlights on SportsCenter like in the past to consume to whatever you cared about.

And then the big kahuna: The speed of life has quickened its pace so much that there's an argument that the game doesn't match.

When I bring my kids to a baseball game, the sport is eating — not watching — the game.

They like hockey. It's non-stop. It matches how their brains process things.

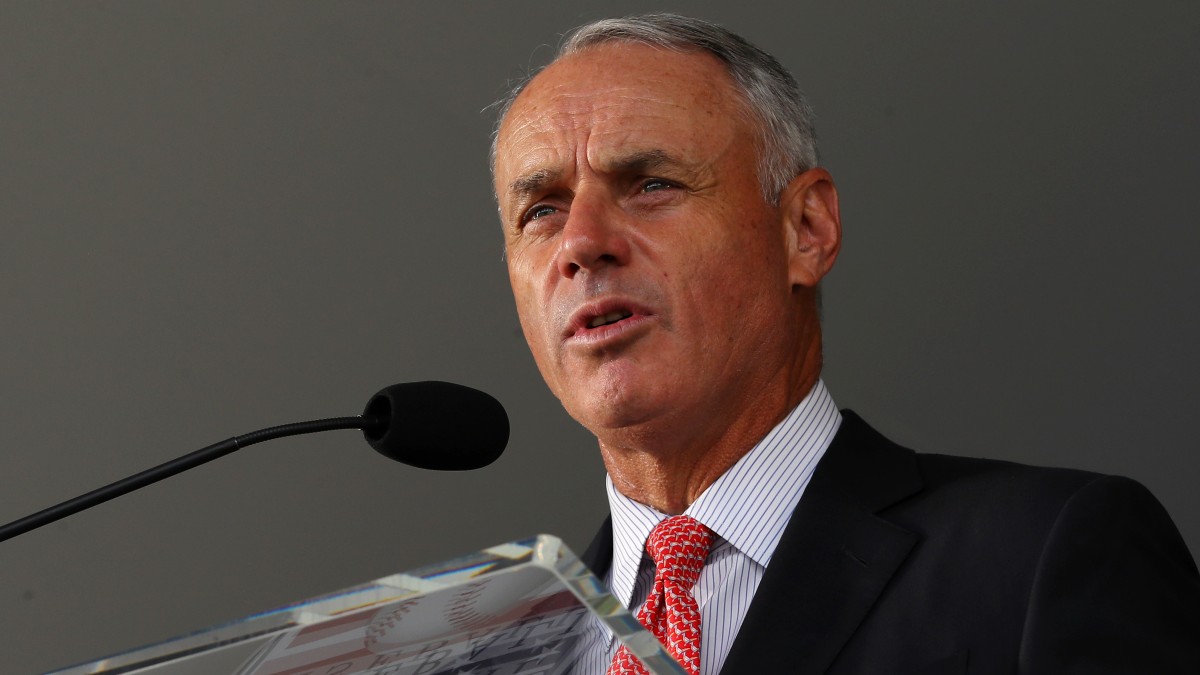

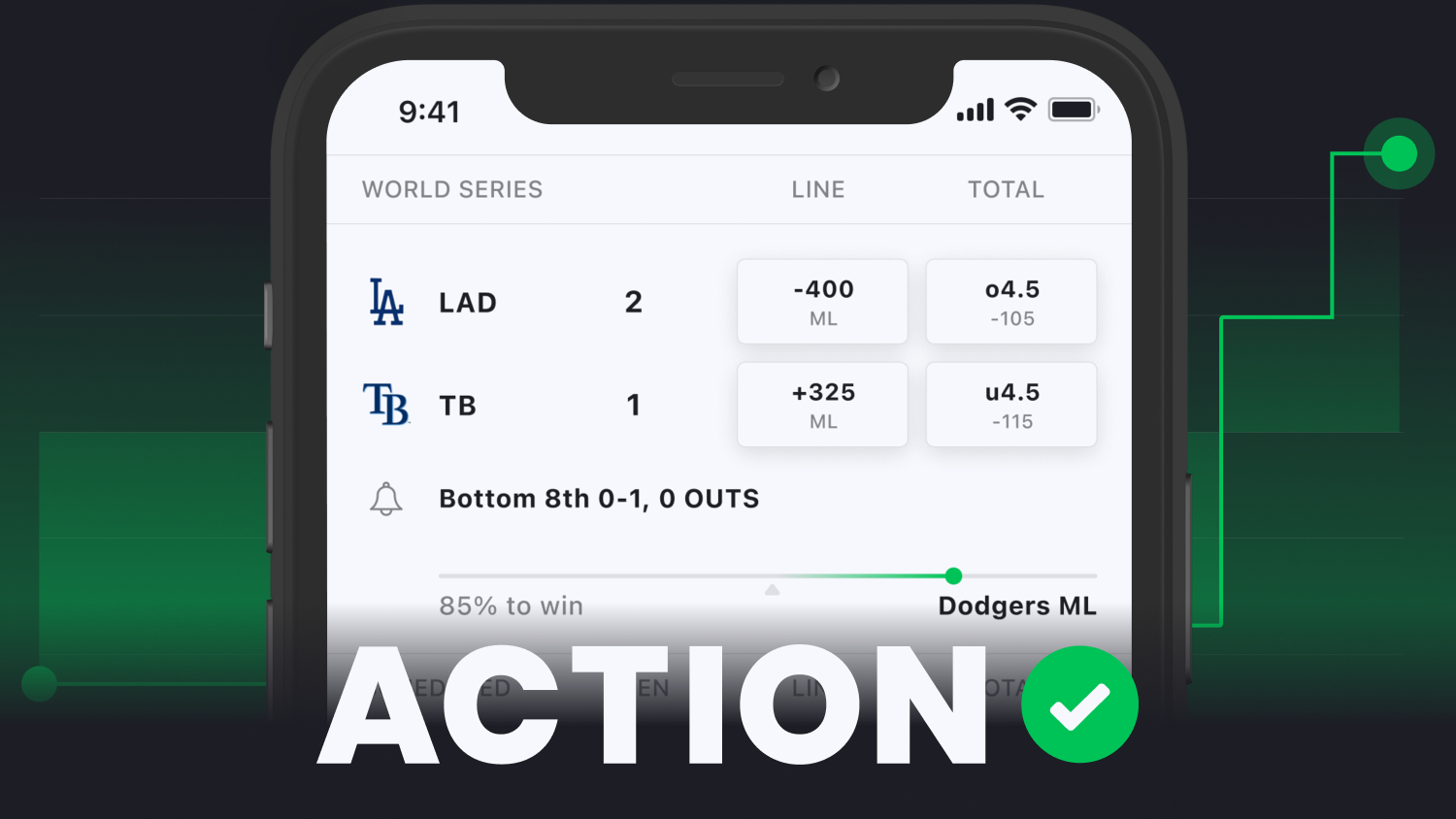

As MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has freely admitted, the availability of gambling allows for time for bettors to make decisions, which, in turn, shifts the idea of the slow-game into a positive.

Some will say baseball can't suffer unless what happens today is what happened in 1994 — the loss of games.

I disagree.

Baseball finds itself fighting hard for relevance every day. And as the clock ticks, with no timetable on next season, the further the risk of the sport declining.

In 1995, we could easily go to another sport that appealed to us; that's what happened to me.

In 2022, baseball risks losing fans to a lot more than another sport. The amount of things we can now do with our time to fill the excitement that being a fan provides is immeasurably more than it was back then.