There aren’t a lot of popular NBA betting theories that have really made it to the public. I guess recently everyone just bets on LeBron James in the first round (ouch, if that was the case for you Sunday). One theory that I heard a number of times as I was learning about sports betting was the vaunted “zig-zag theory." I’d be watching a game with friends, co-workers or gamblers, a certain result would come in and invariably someone would say “Yeah man, zig-zag theory. You didn't know?" As if that was that, and I was stupid for believing anything different. In order to emphasize how I feel about concepts such as this one, here's an anecdote:

Every Sunday a few years ago, I’d go play craps at Mohegan Sun, a casino nearby. On Sunday afternoons, there were a good mix of crusty old curmudgeons, locals and random New Englanders. The lengths to which the old craps players would go to insist that superstitious things affected the rolls always amazed me. For example, if someone sneezed, and then a player rolled a seven (causing everyone betting on that player to lose their money), people literally blamed the sneeze. Some old guy would always stare at the person who sneezed, and throw up his arms as if to indicate, “OF COURSE YOU HAD TO SNEEZE, YOU RUINED EVERYTHING!” I think I enjoyed these responses almost as much as the actual playing of the game. The best part is, all of the OTHER people would half-nod, as if to say, “Yep, sneeze, that was what caused it. Happens all the time.”

I should also add that these were adult humans … actual adults.

Basically, people looked for anything possible to explain how a hot roll finally came to a halt. The most common eventuality people believe is when the casino changes the stickman — a casino employee who operates the game on a roll-by-roll basis — it impacts the game significantly. Something like, “Ohhhh of course, new stickman, now of COURSE a seven will come."

This is an example of confirmation bias, where we remember things selectively. People don’t remember the 100 other times that someone sneezed and everything went normally, but they recall with great accuracy the time when a sneeze seemingly cost them hundreds of dollars, and when it happens the next time, it will seem like it ALWAYS happens that way. We’re wired this way as humans.

And that’s how I always felt about the zig-zag theory, which states when a team loses in a game of a postseason series, you then bet on that team to cover in the following game. So, for example, since the Cavaliers lost Game 1 against the Pacers, you bet on them to cover in Game 2. Anyway, I always felt like when this theory actually happened, everyone would nod and mutter, “Yep, damn zig-zag theory again,” like with the sneeze at the craps table. But then the hundreds of times it didn’t come through successfully, no one acknowledged the theory even existed. At least, that’s how it seemed to me, but I’m human, too. I think there also is some element of logic behind the theory that makes it believable, that when a team fails to cover, it receives less respect from oddsmakers the next game, and it exceeds those low expectations.

So finally, I just had to know … is there any merit to this thing whatsoever?

Using BetLabs, I went back to look at every postseason series in their database, games 2-7 (since game 1 would have neither a zig nor a zag to go off yet), where the team had lost their previous game SU.

The answer was actually more interesting than I thought.

You see, before last season, the zig-zag theory may have actually made some people money … maybe. Using just those parameters, and again, prior to last season, teams off a straight-up (SU) loss covered the spread 51.3% of the time (415-395-22 overall). Not great, but it’s something. It becomes more profitable if the team you are playing off a straight-up loss is at home (2.6% ROI).

But as you no doubt saw, I kept excluding last season.

And that’s because last season killed the zig-zag theory. It is no more.

Last season, teams off a SU loss in the same series went 21-42-1. Things started zigging and zagging in ways that people weren’t expecting apparently. That year of results basically sapped any profit, ROI, winning percentage, etc. from the previous decade-plus. It went from something that, maybe, won you a tiny bit of money, to something that you absolutely lost on. But at least you get to keep hearing people say things like “yeah, man, zig-zag theory … you didn’t know?” and having everyone still nod.

Let’s change the parameters a little: what about a team coming off an ATS loss instead of a SU loss? So, maybe the team didn’t necessarily lose, but it didn’t play as well as we expected it would, and hey, maybe there’s value there the next game?

The same general answers come back. It was, by the absolutely smallest of margins, a system that covered more often than not since 2004-2005 (52%), until … that’s right, 2016-17. Factor last season in, and you have a -0.3% ROI, and you’ve got nothing to show for all your zig-zags.

Just like with anything in this realm, the more nuance you add, the more you might be able to find an edge. Maybe there are teams that play particularly well off a loss because of their coaching and adjustments, or their role players play much better at home in those spots. But as a general concept, just zigging and zagging doesn’t get you anywhere.

So although it’s possible that for some stretch there were people making actual money off playing this type of thing, the reality is, over the course of the last two decades, it’s been about as predictive as a sneeze at a craps table.

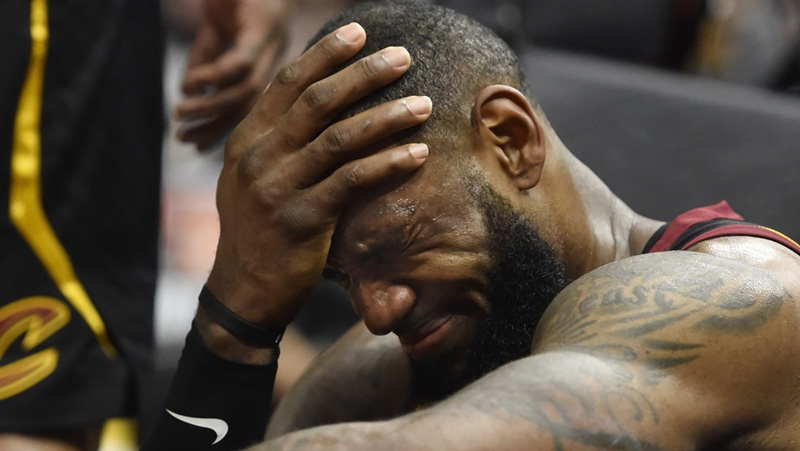

Top Photo: Cleveland Cavaliers forward LeBron James (23) reacts after getting fouled by Indiana Pacers guard Lance Stephenson (not pictured)