- The last time LeBron James was not in the playoffs was in 2005, his second season at 20 years old.

- Now at 34, is this just a blip? Or is father time catching up to the King?

- Rob Perez (@WorldWideWob) and Bryan Mears look at how other superstars have aged and what that might mean for LeBron's future.

WOB: You hear it everywhere you go.

Wake up one morning with sore knees for absolutely no reason? Someone is there to tell you, “father time is undefeated.”

Yawning at the bar after one drink? Father time is undefeated.

Can’t quite hoop like you used to? Father time, you guessed it, is still undefeated.

Let’s focus in on that last question for a moment because it is as relevant as ever after what recently transpired at Madison Square Garden between the Los Angeles Lakers and New York Knicks.

To the surprise of few, the Lakers season has fallen on its face. What was not expected, however, is father time catching up to LeBron James in Year 1 — especially after the unfathomably impressive playoff campaign he completed less than one year ago.

Before we continue, understand this: LeBron James is not washed. He has not graduated from the Carmelo Anthony school of robes and slides in the bodega yet; he’s still merely a freshman. But when LeBron gets erased by … squints … Mario Hezonja at the buzzer in a one-point game, using his patented hard-drive fadeaway off one foot, elevating off the ground with the same verticality a walrus has when he’s flopping on the sand …

… it triggers the “he’s getting old — is he still the best player in the world?” conversation we all knew was coming at some point in the near future, just not this soon.

Instead of writing another 1,000 hot take words on LeBron’s washedness, which will surely be the A-block of talk radio for the next calendar year, let’s research some historical context. At one point, all of the game’s greats surrendered to father time — Jordan launching bricks on the Wizards like he was paid on commission, Hakeem’s lactose intolerant Dream Shake, Kobe’s jumper looking like Carlton Banks after coming back from his surgically repaired Achilles. There is no shame to be had.

- When did these stars and the game’s other greats “lose it'?

- How did they lose it?

- What are the most popular symptoms of a generational talent being infected by father time?

- How does LeBron compare to the field?

Let's dive in.

Historical Superstar Aging Trends

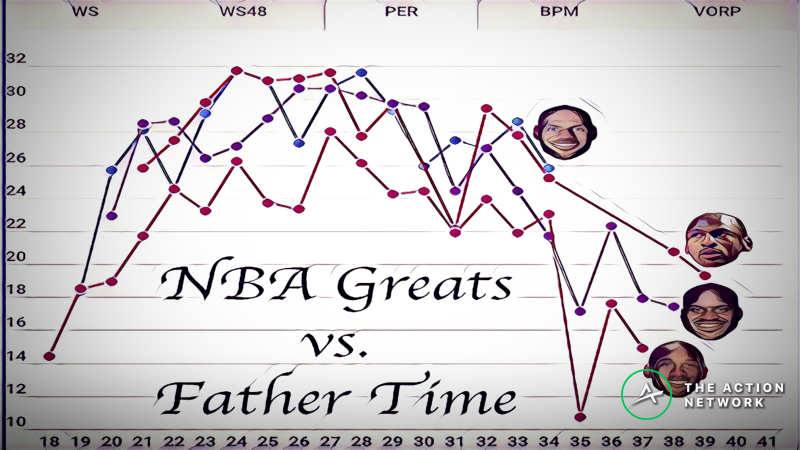

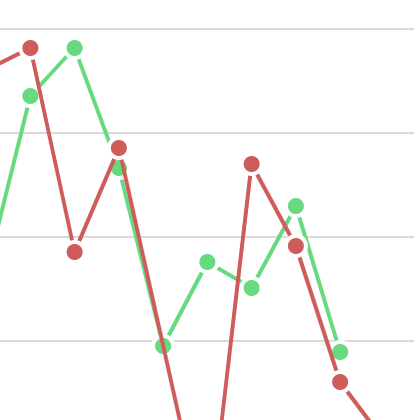

MEARS: Based on a sample of 20-ish superstars, I compiled their average performance in a variety of metrics — Win Shares, Win Shares per 48 minutes, PER, Box Plus-Minus (BPM) and Value Over Replacement Player (VORP) — by season age. Here are the results:

As shown in the chart, players typically approach their prime in their age-24 season and then are smack in the middle of it from 25-29. The first drop-off from their prime came on average at their age-30 season, which means we should start seeing some shift in the Western Conference, as the best players are all around that age: Stephen Curry, Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook are all in their age-30 seasons, and James Harden is 29.

There's a slow decline at 30 years old, and then there's another sizable drop in production at that age-34 season, which coincidentally is exactly where LeBron James finds himself this season.

After that, it gets ugly quickly.

In fact, only four players ever have posted a double-digit Win Share season in their age-37 year or later:

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: 37 (11.2 WS), 38 (10.8)

- Karl Malone: 37 (13.1), 39 (11.1)

- Robert Parish: 37 (10.0)

- John Stockton: 37 (11.2), 38 (10.8), 39 (10.7)

Of note, those players started their careers much later than the league's best players have these days. LeBron's first season came at 19; Kobe Bryant and others started at 18, for reference. The three players listed above all started their careers at 22 or older, which means by 37 they had far fewer total minutes played than LeBron will at that age.

Honestly, LeBron's performance this year isn't far off from other superstars at their age-34 seasons: His Win Share mark is right in line with 34-year-olds like Tim Duncan, Charles Barkley, Larry Bird, Hakeem Olajuwon, Scottie Pippen, Dwyane Wade and others. Of course, LeBron isn't compared to those guys; he's compared to Michael Jordan.

Jordan's age-34 season was his last meaningful one in the league: In that season he posted 15.8 Win Shares, and the Chicago Bulls finished off their third three-peat with a 4-2 NBA Finals victory over the Utah Jazz. Of course, he did return with the Washington Wizards for his age-38 and -39 seasons, and those were far below his career levels. We largely saw him end his career at LeBron's current age, and it's possible that decline would've started the following season if he had continued to play.

Here's LeBron compared to some of his historical peers.

(Note: the graph is interactive, so hover to see an individual season or click to remove a season.)

Again, LeBron is always going to be compared to MJ, who had a ridiculous mid-30s run. But that's historically incredibly rare and something that might just not be possible in the current era of basketball that is loaded with other superstars.

Other than MJ, LeBron is right in line with the general aging curve of other players, even superstars.

Of course, this type of analysis isn't perfect. There are different types of players, and those types may age differently. For example, some of the best late-career seasons came from big men like Karl Malone and David Robinson.

First, again, those players started much later. Robinson, in fact, didn't begin his NBA career until his age-24 season. And second, because of their eras and the way basketball has evolved, those players relied on athleticism far less than modern bigs and wings have to. It's very possible that the aging curve is going to be steeper moving forward for all players given the NBA's evolution.

It's also tough to measure because of injuries. Some players just get worse because of declining athleticism; others get worse because of more injury concerns. It's more difficult to recover from an injury — and injuries happen more frequently — in older age, and that likely starts or accelerates the aging curve.

We've seen a hint of that this season from LeBron, who has been Iron Man for his entire career but missed a chunk of time with a groin injury. He was still declining this year, but it's possible if that hadn't happened the Lakers would be in the playoff mix and LeBron's decline wouldn't be such a national story.

But alas, here we are. LeBron will miss the playoffs for the first time in forever, and people are wondering whether this is a blip on the radar or a signal of things to come. The data says — unfortunately for Lakers and LeBron fans — that things are more likely to get worse than get better.

That doesn't mean LeBron can't have a better season next year, especially if he has better injury luck and superior teammates. But if I had to bet — and we're a betting company, after all — I would bet that LeBron's best seasons and playoffs heroics are in the past, not the future.

WOB: OK, first of all, as the self-appointed leader of Team Eye Test — let me reiterate that these are just numbers and tell only half the story. With that said, holy crap Michael Jordan and LeBron are nearly IDENTICAL in efficiency at this point of their careers:

Second: Shaquille O'Neal remains egregiously underrated in regards to "the best player of all-time" conversation. I'm not crazy enough to sit here and argue that he is, but when you look at his sheer dominance from an advanced analytics standpoint — it's truly jaw-dropping.

The peak of his career was as preeminent as any human to ever play the game, and he has rings to back it up. That is indisputable. What is disputable is where durability ranks on your prioritization list of "best player" prerequisites. Shaq didn't do it for multiple decades, but my god, just look at his numbers compared to the other game's greats.

Third: Kobe. 😪

Fourth: It is rather clear Father Time hit Father Prime (Dwayne Wade) harder than any NBA great in history. My goodness, that is a double black diamond ski slope across the board.

Lastly: LeBron is the gold standard. The fact that he's been able to perform at these levels for as long as he has is unequivocally one of the most impressive achievements of durability we have ever seen in professional sports. However: excluding the outliers of the 38+ samples, the biggest drop-off in efficiency/win shares/production for the NBA's greatest players happened between the age of 34 and 35.

LeBron is currently 34.25 years old, and he has looked every second of it at the end of this 2018-19 regular season campaign.

Maybe he's truly immortal and just taking these months off because he knows his team isn't going to the playoffs. It's a legitimate hypothesis considering he didn't miss a single game last season and has fought on the front lines of a basketball world war for the past 10 years. A little R&R is certainly deserved.

But there is a chance he thought he could just use his evergreen athleticism to elevate over Mario Hezonja with that one-legged step-back finishing move we've seen throughout the years. It didn't happen, and my initial feeling after analyzing his reaction tells me he looked as shocked as we did.

That wasn't supposed to happen. That never happens. What the hell just happened?

We won't know for some time if this was just an aberration or if where there's smoke there's fire … which is why I implore you, right now more than ever, to cherish it — to cherish him — because the washedness monster is coming, and father time spares no soul.