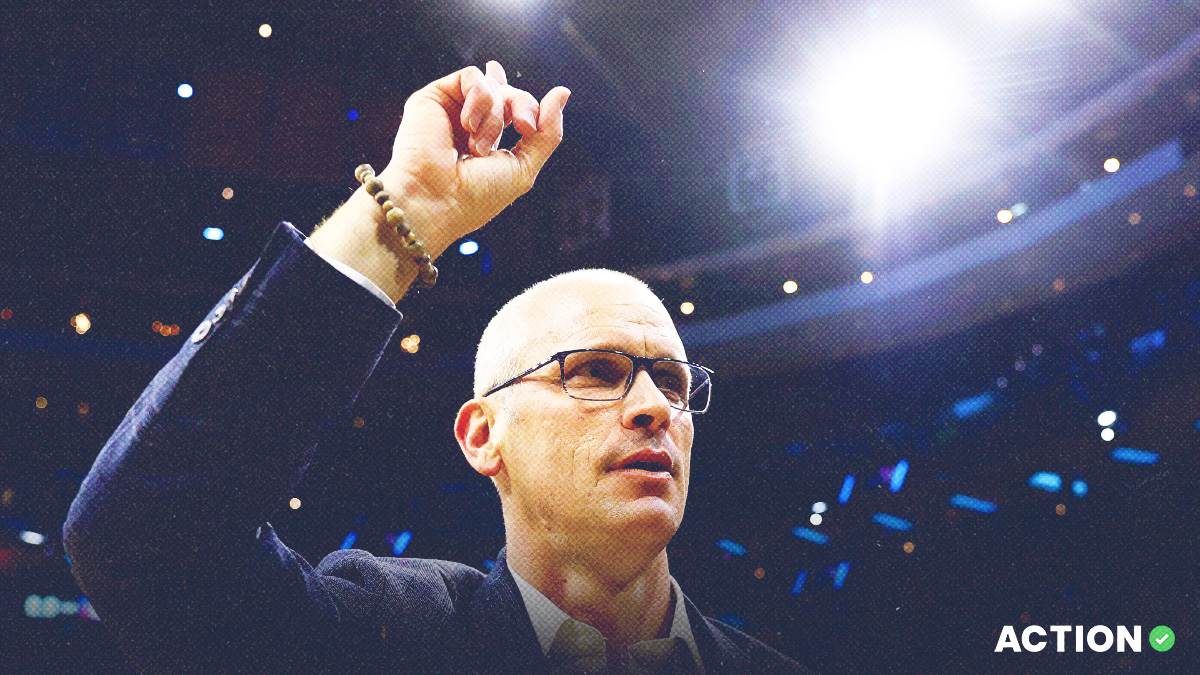

Whenever I think of this era of Connecticut basketball, I always think about one play.

Dan Hurley’s hiring in 2018, the return to the Big East, the two first-round exits, the dominant National Championship run – it all comes rushing back when watching this play.

Last year’s Storrs' sharpshooter Jordan Hawkins — who now plays for the Pelicans — scored 154 points running around off-ball screens in 2023. Only Nevada’s Jarod Lucas scored more that year.

In this play, Hawkins sprints around three off-ball screens while covering nearly the entire width of the half-court twice. Eventually, the career 38% 3-point shooter got a relatively clean look, which he canned.

Watching this is equal parts dizzying, mesmerizing and satisfying. It looks so simple – just a guy running around the court until he finds an open piece of floor – but it’s intensely complex and, more importantly, challenging to combat.

This play encapsulates the subject of today’s column: UConn’s pattern motion offense.

What Is A Pattern Motion Offense?

Let’s start with the basics.

Motion-based offenses are predicated on ball movement and player movement, utilizing secondary off-ball actions to generate secondary off-ball creation, shooting and scoring, thus simultaneously de-emphasizing on-ball dribble creation.

As such, these schemes rely heavily on off-ball screen, hand-off and cutting sets to pop open perimeter shooters or hit rim-runners.

I.e., Players move, the ball moves and someone gets an open shot without too many dribbles.

And, as Coaches Clipboard describes:

“Patterned offenses require players to run a specified pattern of movement, screens, cuts, passing, etc. There is continuity or continuous flow from side to side.”

So, when you imagine a pattern motion offense, think about motion-based set plays with initial secondary off-ball actions that continuously funnel into more secondary off-ball actions when the first look isn’t there.

As an aside, it’s worth mentioning that pattern and continuity are essentially interchangeable terms. Continuity motion offense and pattern motion offense are more-or-less the same thing.

If the team runs an off-ball screen to pop open a shooter on the right side of the court, but he’s ultimately covered, the offense can run the same action on the left side. If the second look isn’t open, the shooter can quickly pop the ball to a cutter running to the rim.

If that isn’t open, the cutter can kick the ball back to the perimeter and into another off-ball secondary set. They will keep doing this side-to-side, inside-to-out until somebody finds a shot.

A great example is the flex motion offense, which Rick Barnes runs with Dalton Knecht at Tennessee.

The flex motion is a pattern-based offense where most off-ball screens come between the low block and the adjacent corner. The scheme primarily generates at-the-rim buckets from cutters or elbow jump shots.

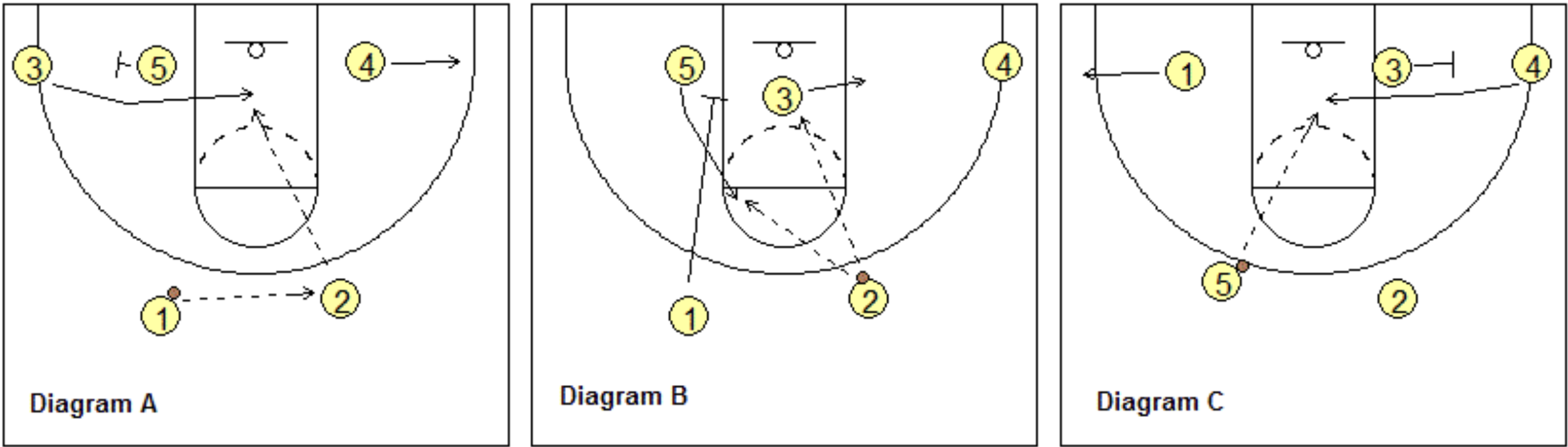

Check out the Xs and Os below:

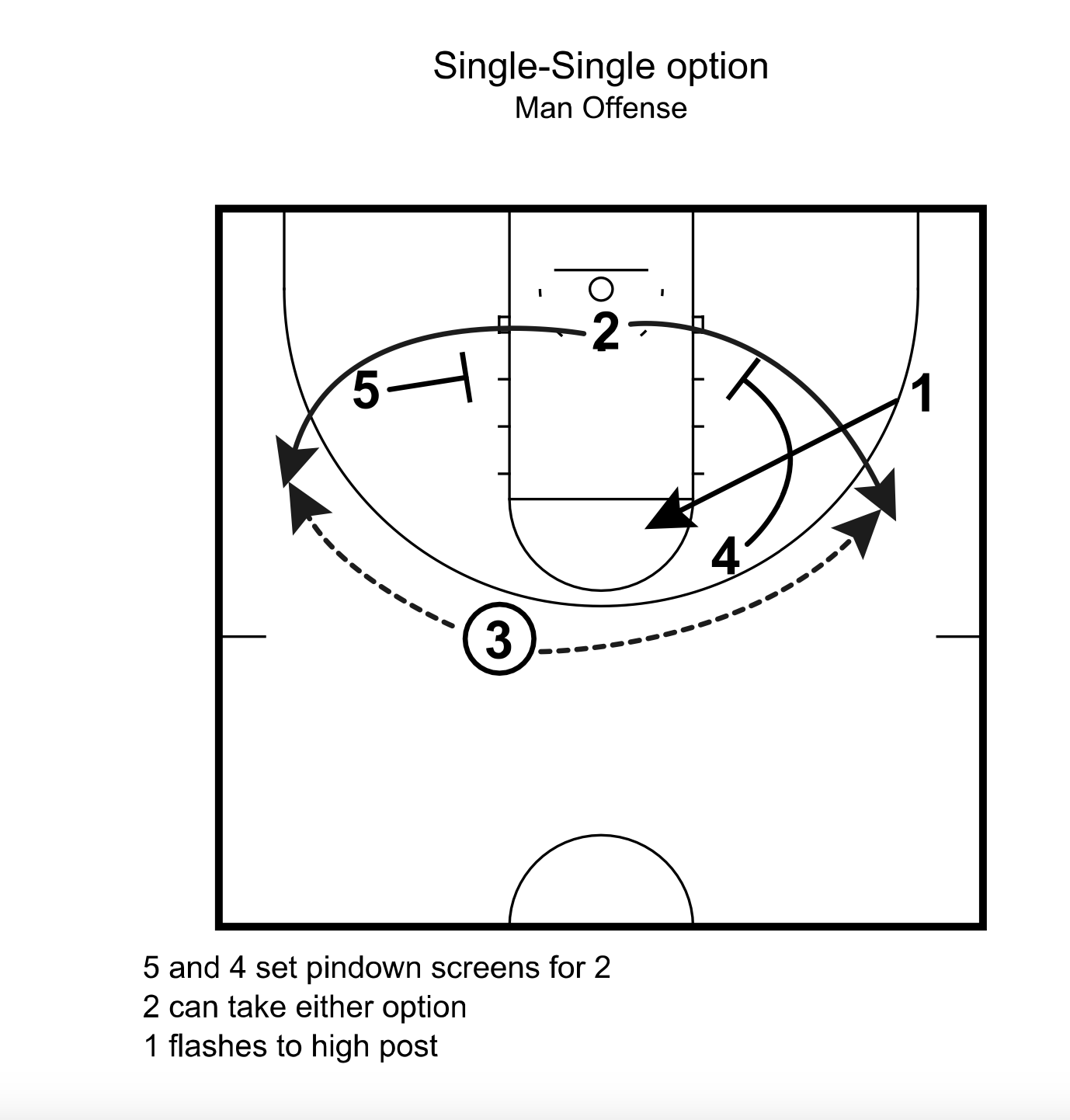

Option one is for 2 to hit 3 cutting off the flex screen set by 5. If that’s not open, 1 will set the down-screen for 5 and 2 will hit 5 at the left elbow. He can take the shot or look to hit 4 cutting off the flex screen set by 3.

And if that’s not open, 2 will set the down-screen for 3, bringing us back to the initial set.

The motion continues left and right ad infinitum, or until the shot clock runs out.

Here are a few examples from Knecht himself:

Both actions have him coming off flex screens across the baseline. He posts up for a fadeaway in the first one and takes a near-the-break catch-and-shoot 3 on the other.

The two squads run similar structures, but Tennessee’s offense pales compared to UConn’s.

Yes, UConn runs a pattern motion. But the Huskies run a series of elaborate, varied, complicated set plays and Hurley’s playbook is as deep as the Atlantic.

UConn’s ridden a pattern-motion-on-steroids attack to a National Championship.

I’m going to explain how.

Shout-Outs

I’d like to highlight two analysts whose knowledge and content I always leverage in my analysis.

First, a huge thank you to Jordan Sperber of Hoop Vision. I can’t recommend his content enough, so please follow him on Twitter, subscribe to his YouTube and read his Substack.

Second, a shout-out to Jordan Majewski of Staring at the Floorboards. He’s arguably the best Xs and Os writer in the college hoops content space, and I thank him for his shared expertise.

UConn’s Staggers

In my opinion, UConn’s off-ball screens are the most crucial aspect of the offense and the basis for every half-court point scored.

And relative to the national average, the Huskies run off-ball screens more than any other offensive set. They’ve taken over 130 shots coming around off-ball screens (top-25 nationally) and generated over 1.00 PPP on those actions (top-90).

Specifically, UConn runs around stagger screens a whole lot – stagger screens are essentially double off-ball screens where a Husky will run around two consecutive screeners.

Here’s an excellent example from Hawkins in last year’s National Championship game:

Hawkins comes across the baseline. As he approaches the left corner, Alex Karaban sets the first screen while Adama Sanogo sets the second screen. Hawkins loses Lamont Butler through the chaos, generates an open top-of-the-arc 3 and buries it, essentially closing the door on San Diego State’s title hopes.

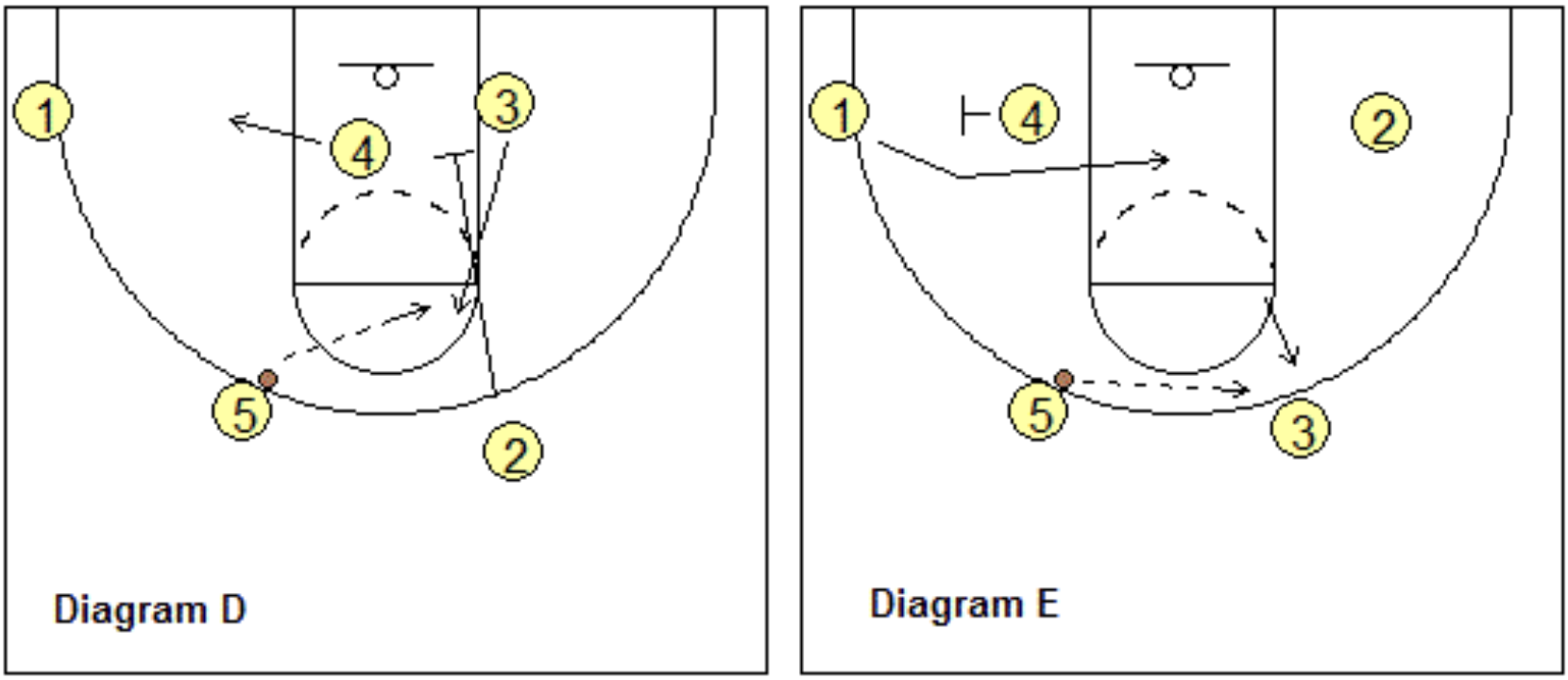

This set is known as Delay Floppy Gut Stagger, and it’s actually consecutive stagger screen sets. Tristen Newton gets the dribble hand-off from Sanogo at the top coming off the first stagger screen set by Naheim Alleyne and Karaban, and then Hawkins follows.

The Huskies run consecutive stagger screens all the time, whether on the same or opposite sides of the court, feeding continuous player and ball movement until something becomes available.

And, as you can see in the chart above, UConn would’ve slipped into a high pick-and-roll set if Hawkins hadn’t been popped open. Again, continuous player and ball movement.

Here’s an excellent example of a similar scenario from last year’s Big East tournament semifinal game:

Alleyne comes off the first stagger screen on the left side, nothing doing. Hawkins comes off the second stagger screen on the right side, nothing doing. Hawkins flips it back to Newton, who flows seamlessly into a ball screen (more on that later) with Sanogo and eventually finds Alleyne for a corner 3.

So much of UConn’s offense starts with these off-ball actions. Whether it be down screens (chest toward baseline), back screens (behind defender), flare screens (away from the ball) or flex screens (as talked about), the Huskies fuel motion through secondary sets. Stagger on one side, stagger on the other, keep it moving.

But the motion doesn’t stop there. Instead, UConn will mix it up off the initial set, opening the playbook to misdirection screening actions, dribble hand-off sets, cutting actions and rim duck-ins.

Off-Ball Screening Misdirection

Look, the guy doesn’t have to come straight off his teammate’s shoulders when running off-ball single or stagger screens.

In fact, you must provide variations on these sets to counter different defensive coverages.

Nobody does that better than Coach Hurley.

There are countless sets I could run through, but I’ll dive into a few.

But before I start, I need to emphasize one thing: These are all set plays. Hurley designs these plays in his lab, and it's the player's job to read and react to the defense in continuity if the first option isn't available. His playbook is deep, and the players make it deeper by flowing into different actions off initial sets.

Anyway, let's start with Twirl actions.

Check out this play from the Jan. 10 game against Xavier, courtesy of Jorden Sperber of Hoop Vision:

Stephon Castle is about to come off the stagger set by Karaban and Samson Johnson when – wait! – Castle twirls around and sets a screen on Karaban’s man, and he ends up running off Johnson on the initial stagger screen for a wide-open jumper.

Here’s a similar play from the Jan. 17 game against Creighton:

Creighton’s Steven Ashworth fully expects the sharpshooting Cam Spencer (42% career 3-point shooter) to rip off the Karaban-Johnson stagger screen, only for Spencer to twirl and set a screen on Karaban’s man, absolutely flummoxing Ashworth in the meantime. Karaban runs off the Johnson stagger and gets the open look.

Connecticut’s pattern motion is partly designed to confuse defenses. It’s tough to keep up with the quick and crisp player and ball movement (not to mention it's just tiring chasing shooters down all the time; have you ever covered an off-ball runner in pick up?), and the Huskies will exploit any mistake, including the one made here by Creighton’s point guard.

Here’s another variation: I’m unsure what to call, so I’ll name it the Reverse Twist.

Hawkins comes off a Jackson-Sanogo stagger and clears out to the weak side. But then Hawkins and Karaban run a twist, with Hawkins reversing the floor across a Sanogo screen. Iona’s Walter Clayton Jr. has no shot of keeping up, and the open 3 is money.

Let’s discuss another variation I love trying to pull in my local pick-up games: Ghost screens.

Ghost screens are essentially fake screens. A player will pretend to set a screen for the ball-handler, only to pop out into open space.

Here’s Karaban ghosting a ball screen for Spencer in the Dec. 5 game against North Carolina, baiting two Tar Heels into tagging Spencer and eating up the open space for an open 3:

It’s like pick-and-pop, just without the pick.

I adore this play from last year’s Sweet 16 game against Arkansas:

Hawkins ghosts the screen for Andre Jackson Jr., and Jackson “takes” the screen and dribbles to the right logo. Hawkins and Alleyne then twirl each other, with Hawkins sneaking around an off-ball screen from Sanogo, getting the pass from Jackson and driving the open lane.

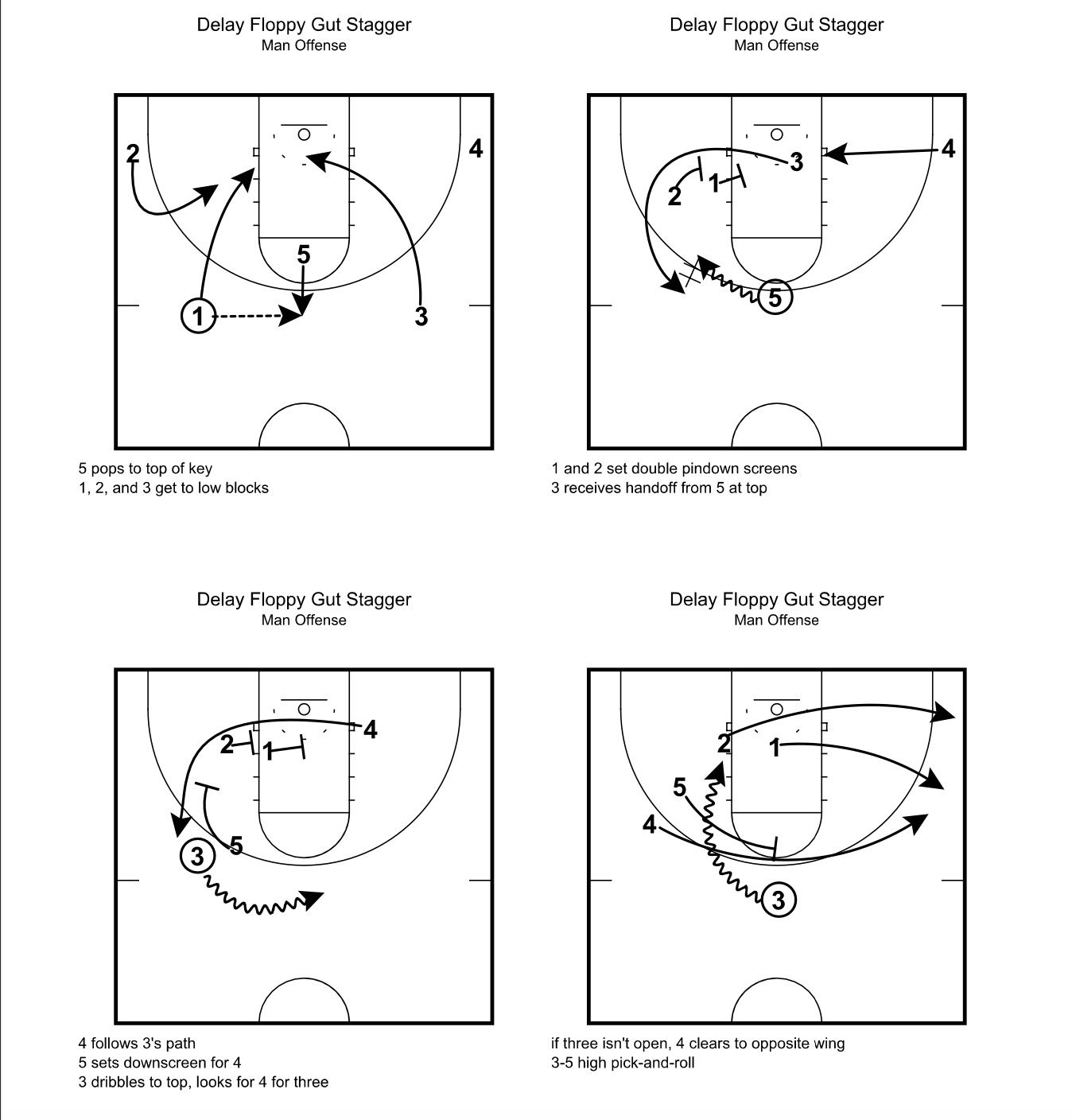

UConn calls this play the Double Ghost Double Bilbao:

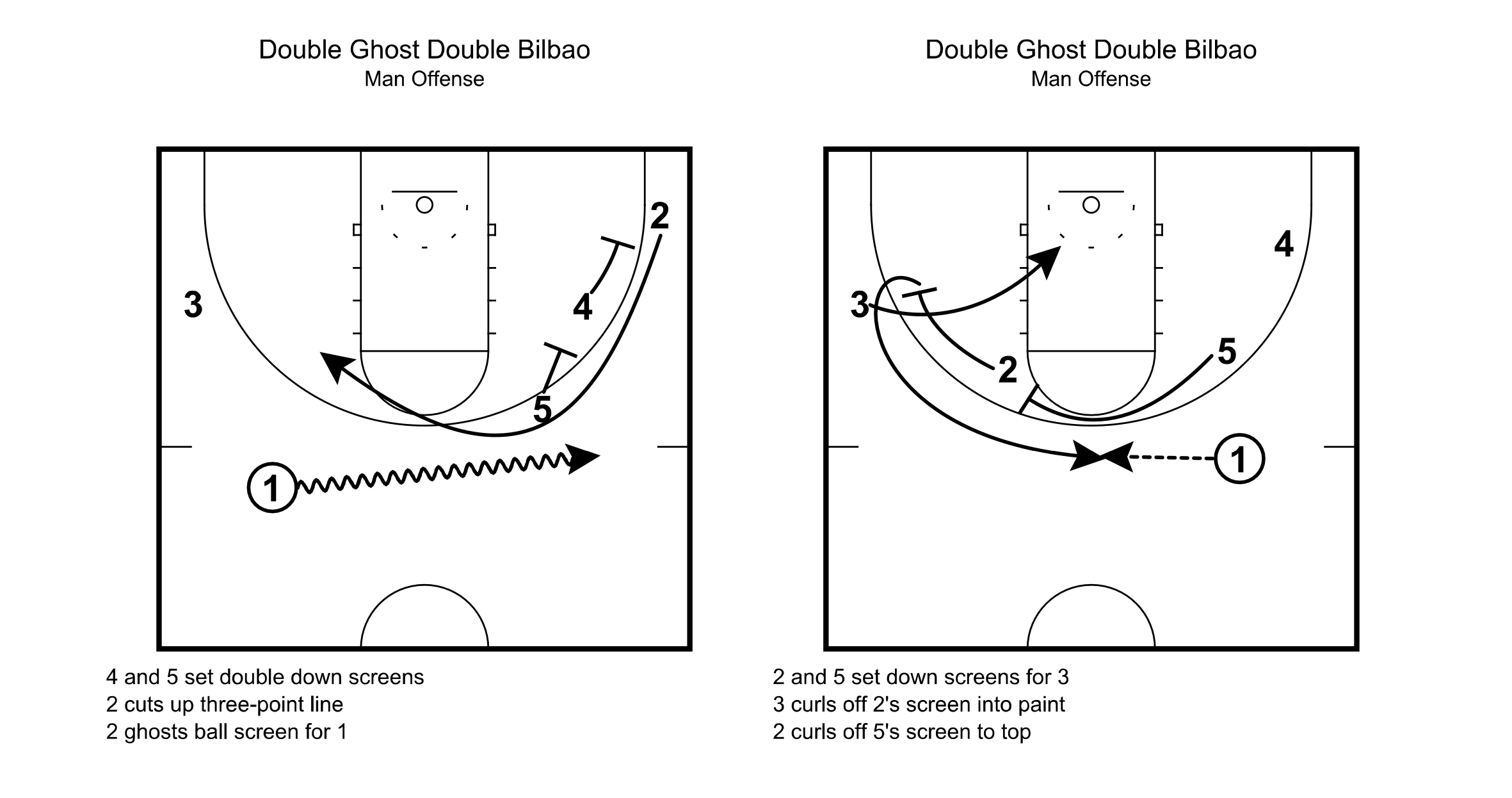

Another basic variation is Floppy, a set used widely across all levels of basketball. Floppy action is putting a great shooter off-the-ball under the basket and giving him two off-ball screens on either block, so he can take either option trying to pop open for a shot.

Here’s an example from UConn’s Elite Eight game against Gonzaga last year:

Hawkins almost takes the left-elbow screen from Donovan Clingan but opts instead to run off the Karaban screen on the other elbow, and he gets the open look at the right break.

And one more bonkers example from the people over at The Hurley Basketball Think Tank:

Did you see what happened there?

This is called a BLOB (base-line out of bounds) Triple Stagger Twirl, and the film is from the Dec. 5 game against North Carolina.

Solomon Ball comes off the triple stagger set by Spencer, Karaban and Clingan. But Spencer then fakes like he’s coming off a Karaban-Clingan stagger before twirling and setting up a Spencer-Clingan stagger for Karaban, who comes off the screens for the wide-open shot.

These are all just different ways to manipulate off-ball movement into open buckets, and Hurley layers these patterned motion secondary screen sets until nobody can keep up. I’m watching these plays at half-speed, part dizzy and part infatuated.

But screw it, let’s go a few layers deeper.

Slipping, Ducking, Cutting

The Huskies rank fourth nationally in 2-point shooting. They score around 38 paint points per game (93rd percentile), shoot 69% at the rim (94th) and generate 1.32 points per shot at the rim (98th).

One of my favorite ways the Huskies generate those interior baskets is by slipping and ducking the perimeter staggers.

Check out this play from last year’s first-round tournament game against Iona:

Jackson and Clingan set a stagger screen on the right side but get nothing. So, characteristic of a pattern motion offense, Clingan and Joey Calcaterra set a stagger on the left side for Karaban. But Karaban runs a twirl for Calcaterra to come off Clingan’s screen, and both Iona defenders sprint toward the 45% 3-point shooter.

So, Clingan slips inside, nobody follows, and there’s an easy dunk.

I love that play because it shows everything that UConn is good at. Elite player movement, elite ball movement and intelligent decision-making in a continuous offensive flow – when the defense adjusts and takes one thing away, there’s always another option waiting.

Just another layer added to the top of Hurley’s off-ball screen cake.

Clingan, Johnson and Karaban always want to slip and flash behind stagger screen defenders, hence why the trio has combined for 167 points on 114 cutting possessions, suitable for a whopping 1.46 PPP.

Here’s another example, this time from Spencer during the Dec. 5 game against North Carolina:

So, Spencer sets a flex screen for Newton, and he probably wants to run off the screen Karaban’s setting on the right side and flash for a catch-and-shoot opportunity near the right break. But Cormac Ryan knows this, so he denies Spencer the screen.

But Spencer happily slips the defender and cuts back toward the rim for a wide-open layup.

Oh, well, too bad, Cormac. UConn knows there’s always another option in the motion.

DHOs

Another classic way for motion offenses to create is through dribble hand-off sets, and UConn is no stranger to those.

Here’s a good BLOB hand-off play involving Clingan and Alleyne from last year’s second-round game against Saint Mary’s (second tweet in thread):

Clingan takes the ball at the top of the key – which is generally how UConn’s DHO plays work – while Alleyne comes off a Karaban down screen. Clingan essentially acts as a stagger screener, and Alleyne’s defender can’t get over the monster 7-foot-2 center, leaving plenty of room for the career 37% 3-point shooter to let it rip.

Here’s a second UConn DHO play revolving around Sanogo from last year’s Elite Eight game against Gonzaga (again, second tweet in thread):

I like this one a lot more.

As Sanogo takes the ball at the top, Karaban and Hawkins run a twirl on the right block, ultimately popping open Karaban for the hand-off from beyond the arc.

In the prior example, the Gael defenders stay under the DHOer, allowing Alleyne to shoot.

But in this example — as we saw with Iona and North Carolina — the Zags overcommit to Karaban, and he adjusts, hitting Sanogo freely ducking toward the rim for a layup.

This play emphasizes everything we’re discussing. Hurley runs a stagger screen variation, which Karaban and Hawkins execute flawlessly. Then Karaban reads and reacts to the defense in motion, hitting the open man in stride.

And I’m sure if the two defenders had tagged Sanogo instead, Karaban would’ve canned the open 3.

That’s smart motion basketball.

Altogether Now

Are you starting to put it all together yet?

Let’s go back to that first play.

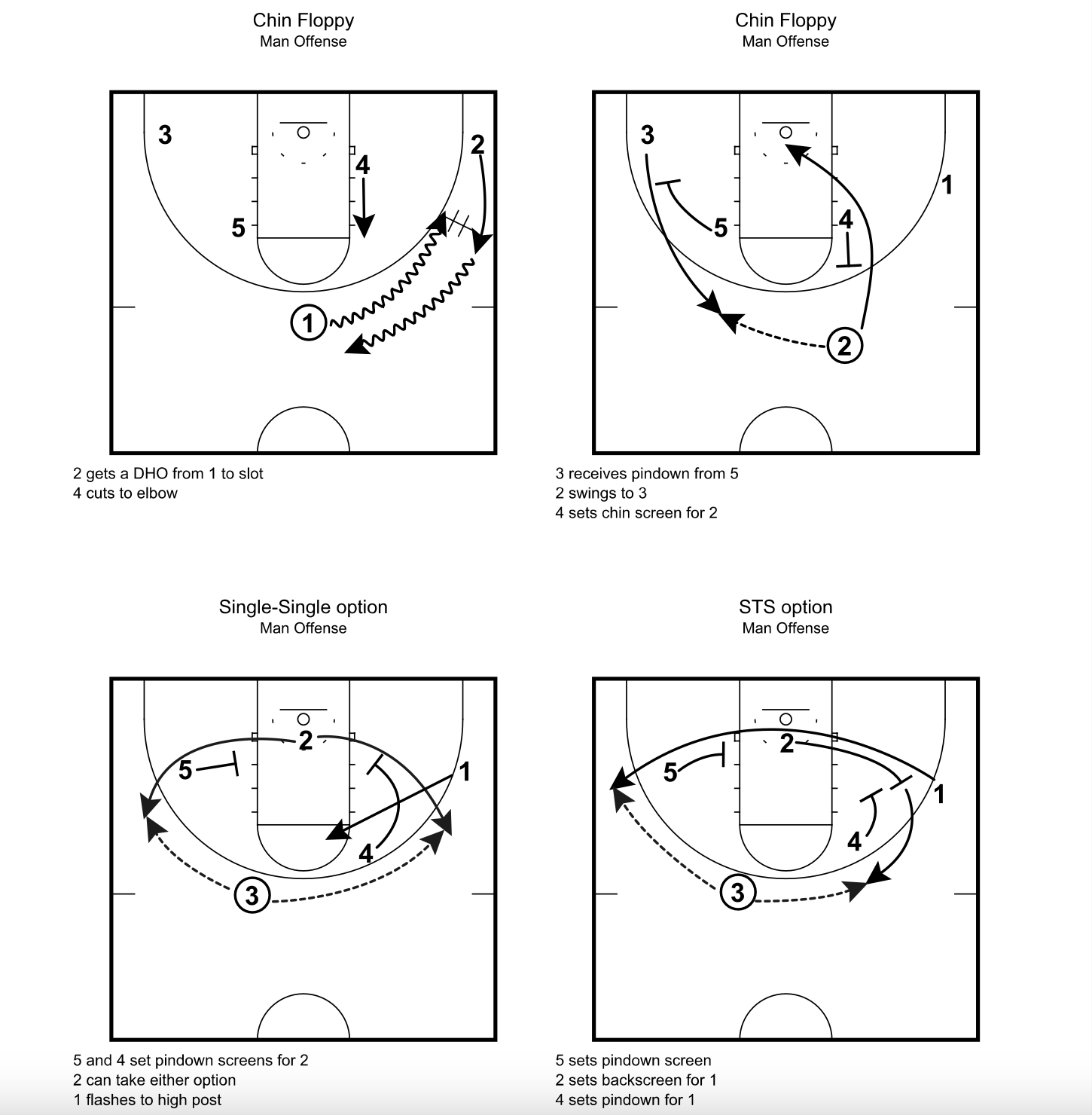

This is no longer some random guy running around, right? This is Hawkins running Chin Floppy twice.

Here’s how the play works:

Newton tosses it to Hawkins and then clears to the corner. Hawkins tosses the ball to Jackson at the top of the key while Karaban cuts up to the right elbow to set the initial chin screen.

Hawkins rolls around the Sanogo screen on the left side, nothing going. So he heads right back to Floppy point A – under the basket – and decides to reverse course and take up Karaban on the other screen.

Continuous pattern motion until…

Boom. Open 3.

However, take a closer look at the end of the play.

Both Gonzaga defenders tag Hawkins for a split second, and Karaban immediately flashes toward the rim. If Julian Strawther doesn’t recover and continues closing out on the shooter, Hawkins would likely hit Karaban under the basket.

It’s everything Hurley’s pattern motion is supposed to be. The play has nearly zero dribbles, as player and ball movement precede dribble creation. After Hawkins finds nothing on his first set, he immediately runs the same play on the other side of the court, emphasizing the pattern motion nature of the set.

And if that shot hadn’t been available, the ball would’ve kept moving to another moving player over confused defenders tired from chasing everyone around for 30 seconds.

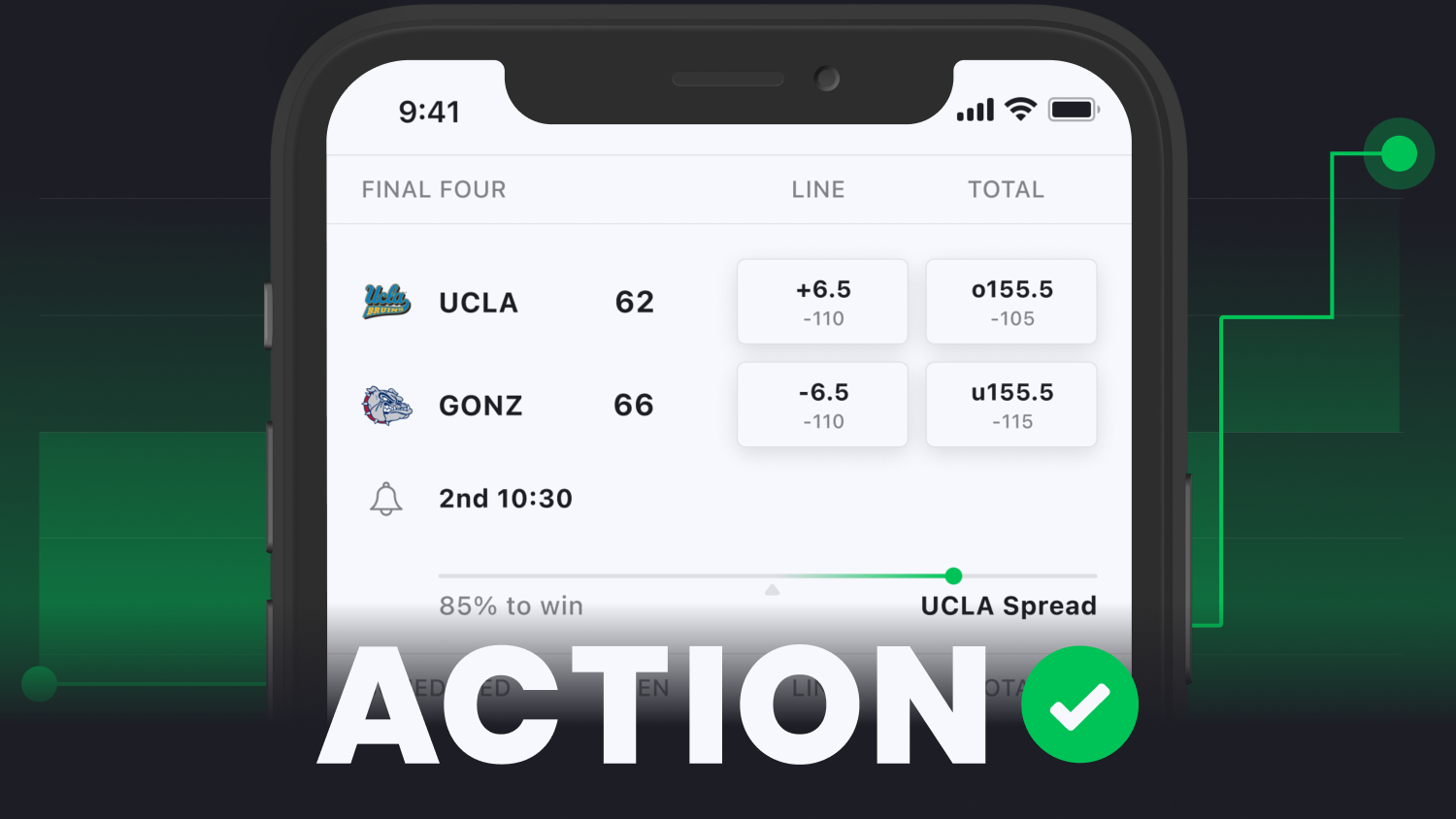

This season, UConn ranks third nationally in offensive efficiency, fifth nationally in eFG% and ninth nationally in assist rate. The Huskies have run 463 off-ball screen, hand-off and cutting actions ending in a shot attempt and have scored 536 points on those attempts, suitable for a whopping 1.16 PPP.

| Set | Possessions/Game | PPP | Percentile Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-Ball Screen | 5.8 | 1.00 | 75th |

| Handoffs | 4.7 | 1.01 | 89th |

| Cutters | 7.3 | 1.34 | 92nd |

Otherwise, the Huskies have used the motion to generate 521 catch-and-shoot attempts, and 61% of those have come unguarded, the fourth-best mark among D-I teams.

The Huskies' 12.1 unguarded catch-and-shoot jumpers per game ranks eighth nationally. It’s easy for Spencer, Karaban, Castle and Newton to shoot the lights out when Hurley schemes them four feet away from their chasing defender.

Hurley’s elaborate, variable pattern motion sets develop high-quality secondary offense and catch-and-shoot opportunities, and the Huskies have been executing player and ball movement to perfection for two straight seasons.

It’s a crazy offense, and Hurley can keep layering secondary variations on top of initial stagger screens until opposing defenses are turned entirely inside out.

And, honestly, my analysis here has barely scraped the surface. I've described the general structure of Hurley’s layered pattern motion offense, but there's barely enough time in the universe to break down every set in the Husky playbook. UConn layers Horns actions, Zoom actions, Tug actions, Indy actions, you name it.

Hopefully, however, you can somewhat conceptualize the offense the next time you watch UConn win.

Can You Stop The Motion?

The answer is yes and no.

It’s easy to generate mismatches and run pattern motion sets against simple man-to-man defenses because it’s easy for UConn’s shooters to confuse and lose defenders around staggers.

But, of course, not every college basketball team runs a simple man-to-man. And different coverage schemes can flummox pattern motion sets.

The best example is Seton Hall. Shaheen Holloway’s switch-everything defense is perfect for stopping UConn’s off-ball screening, as the Huskies are no longer running away from a defender but instead running into another one.

Here’s a clip from UConn's game against Seton Hall in late December:

I found the very first set of the game the most interesting – and hilarious.

Right from the tip, the Pirates use their athletic switch to bother every UConn action.

The initial DHO to Spencer was covered, so the Huskies tried some off-ball screens unsuccessfully, including Newton coming around Clingan on the left side and Spencer coming around Karaban on the right side.

Eventually, the Huskies hit their fail-safe option, a post-up set with Clingan that was ruthlessly denied by Jaden Bediako.

Of course, UConn snags numerous offensive rebounds before eventually finding Newton for an open 3, which perfectly describes how tough it's to stop the Huskies.

Per Jordan Majewski of Staring at the Floorboards, Coach Hurley stopped scheduling Holloway and St. Peter’s because he hates the matchup. Unfortunately, Holloway took the job at the two’s mutual alma mater, and the Pirates have switched everything and stayed with every single Husky movement since.

Earlier this year, Seton Hall beat UConn 75-60 while holding the Huskies to .75 PPP on 41.4 eFG%. The Huskies managed only 15 points on 11 secondary actions – a respectable 1.4 PPP but not enough volume – and stayed close with shooters, holding UConn to 12 points on 19 catch-and-shoot attempts (.63 PPP).

Other schemes that can flummox UConn include St. John’s and Rick Pitino’s amorphous matchup zone — which will pass off secondary motions like a switch-everything scheme — and Creighton’s drop-coverage — which forces opponents into dribble creation by overplaying ball-handlers on the perimeter and secondary shooters on the wings while overprotecting the rim.

Creighton’s drop ripped apart UConn’s motion just the other night. The Huskies managed only 16 3-point attempts and made only three (18%), scoring just 15 points on 18 secondary sets (.83 PPP).

Here’s a good example from early in that match:

So it’s a dribble hand-off play for Newton, who gets the ball after coming off a Karaban off-ball screen. But Ryan Kalkbrenner sags toward the rim while the other defenders remain spaced and tightly knit with the other off-ball players. It leaves Newton wide open in the middle of the floor, but that forces Newton into on-ball creation, which is not UConn’s strong suit. If Newton hadn’t snagged the offensive rebound, the play would’ve ended with that short-handed floater.

I like this example better:

Another DHO for Newton, this time from Johnson. But look at how Trey Alexander is defending the UConn guard – overplaying him on the perimeter, baiting him to dribble to the middle of the floor as Kalkbrenner drops. And the right elbow is wide open, given Jasen Green is mirroring Karaban on the right break. Drop-coverage schemes beg ball handlers to dribble-create in that area, and while good dribble-penetration shot-creating guards thrive against drop, secondary motion offenses get uncomfortable when handling the ball too long.

Newton made the shot, but it was a brutally tough, inefficient fade-away 2-pointer that needed a friendly bounce.

And, of course, there’s this play here:

Creighton hands Castle the middle of the floor, remaining spaced out on the shooters. Kalkbrenner sags, and Spencer almost screens him away from the lane. Alas, the 7-foot-2 swatting machine recovers and embarrasses the UConn guard.

But the Huskies have answers when things go wrong.

For starters, Newton and Spencer have developed into stud ball-screen creators, with the former generating .90 PPP on the sets (75th percentile) and the latter posting a whopping 1.15 (96th percentile). Clingan and Johnson aren’t half-bad as roll-men, either.

As a result, UConn’s pick-and-roll efficiency has skyrocketed year over year.

The Huskies still don’t lean into ball-screen creation much. But it’s a viable bailout option when every pattern motion set comes up short, especially against coverages designed to limit secondary actions and force on-ball actions.

If you remember from earlier in the article, UConn will seamlessly roll from stagger screens into pick-and-roll sets.

For example, this play from last year’s Sweet 16 game against Arkansas:

The Huskies run stagger screens on both sides with nothing happening, so Newton and Jackson flip the ball back and forth before Newton rolls into a ball screen with Sanogo. The big man finds space on the roll and cans an easy layup.

UConn can still score from on-ball action. Although they lost the game, the Huskies scored 36 points on 34 pick-and-roll sets (1.05 PPP) against Creighton.

Another example comes from a two-game non-conference sample this season – the Dec. 1 loss to Kansas and the Dec. 5 win over North Carolina.

Bill Self is among the wisest defensive coaches to ever step on the hardwood, and he perfectly schemed for Hurley’s playbook. The Jayhawks switched everything, a la Holloway’s Pirates, holding the Huskies to 15 points on 20 off-ball screen/hand-off/cutting sets (.75 PPP) and handing UConn its first loss of the year.

Hubert Davis saw this and tried to do the same thing.

But here’s the catch – you must be a highly disciplined switch-everything defense to keep up with UConn’s elite player and ball movement.

Self’s Jayhawks are that. Holloway’s Pirates are always disciplined and smart.

Davis’ Tar Heels aren't as adept. Hurley continued to run its varied pattern motion sets and just waited for North Carolina to make a mistake.

As you can see in this beautiful video from Sperber below, the Heels made plenty of mistakes:

That ghost screen from earlier is a great example:

That’s just a coverage miscommunication from North Carolina. Jae’Lyn Withers wants RJ Davis to switch to Karaban here, but Davis is completely lost.

Not to drag Davis, but here’s another example of him defending way behind the UConn curve:

As Spencer flips the ball to Diarra, Seth Trible switches from the former to the latter. Davis, however, is hesitant on his switch assignment, and a Johnson flare screen blows him up before he fouls Spencer on the triple attempt.

The Heels did their best, but they’re a sub-par secondary defense – they’ve allowed the 10th-most points to off-ball screen sets (116 at 1.1 PPP) nationally – and the Huskies will season and sautee any minor coverage mishap.

When the dust settled, UConn scored 27 points on 18 secondary actions (1.5 PPP) en route to an 87-point performance against North Carolina's "switch-everything" defense.

Utter domination based on total confusion.

Conclusion

Hurley’s Huskies will keep throwing the playbook at you.

If one set doesn’t work, they’ll run a variation of the set, and if that set doesn’t work, they’ll run a variation on the variation.

If the variations don’t work, they’ll work in a different pattern motion set. Or, they’ll flow from a motion offense into a ball-screen offense. Or his players will hunt hi-lo cutting actions with Clingan to find interior mismatches against switching coverages. The players will do all of this within the set-play framework of the offense, reading and reacting in continuous motion offense.

The players will do all of this within the framework of the offense, reading and reacting in continuous motion offense.

Hurley will shuffle his players and the ball around the court like he’s playing chess, looking for an advantage. He’ll up the ante as needed, throwing more complex and elaborate actions at his opponent until he’s exploiting a mismatch or confusing defenders.

And that’s why the Huskies dominated last March.

Can you imagine trying to prep against Hurley on short rest? He’ll always be one step ahead of you with how vast the playbook is and how bright his players are.

It’s only a matter of time until the Huskies find the motion to turn you inside out. Someone will eventually get open, and UConn will eventually find him.