You know the stats.

You’ve checked KenPom daily over the past six months. You have the projected spread and total for the Final Four games and all four potential National Championship matchups.

But, as sports bettors, we sometimes get too wrapped up in the numbers.

Rightfully so. Sports betting is about trading numbers.

However, only three college basketball games remain, and the market is pretty efficient. You have to dive deep to find an edge.

It’s time to look past the stats and investigate the schematic matchups. There might be an Xs and Os edge that you won’t find in the box scores.

Game previews are the crux of what we do at The Action Network, as breaking down individual games and slates from a betting perspective is what our readership values most.

But I’ve been trying to avoid that more, as we have too many talented analysts to keep ourselves locked into this box.

One of my favorite things to do when handicapping is film and scheme analysis, diving deep into how teams play, why they play that way and what that means for us.

And there’s no better time to do a deep-dive film breakdown than the Final Four, where we can thoroughly explore how all four teams play on the court.

UConn in One Line

Unstoppable, complex, variable, versatile offense combined with an impenetrable Cling Kong drop-coverage defense

Offense

If you want to learn everything there is to know about UConn’s pattern motion offense, I highly recommend reading this piece I wrote about in February.

But don't worry, I’ll give you the short-form version here.

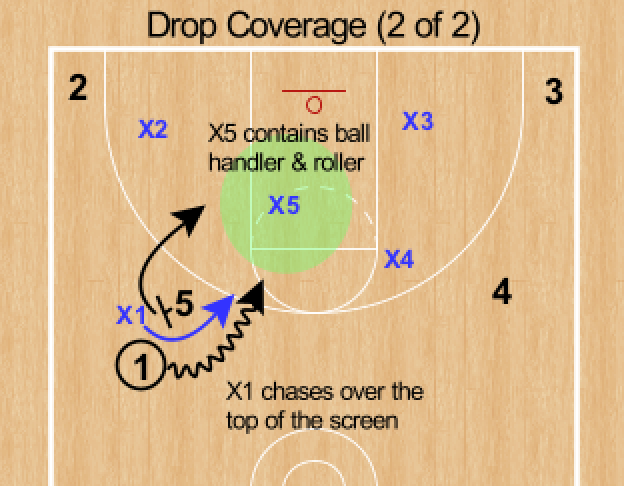

UConn runs a pattern motion offense, predicated on secondary actions emphasizing player and ball movement while de-emphasizing on-ball dribble creation.

The Huskies begin every set with off-ball screens, running them on each side of the court in succession to pop open shooters. If an action on the left side fails to produce a shot, they run the same thing on the other side, hence pattern or continuity.

For example, this play from last year’s Elite Eight matchup with Gonzaga:

Jordan Hawkins runs off three off-ball screens in this set. First, he sprints around a chin screen set by Alex Karaban at the right elbow to get under the basket.

Next, Hawkins rolls into floppy action – hence, chin floppy. Floppy is a common set run at all levels of basketball, where you put a shooter under the basket and give him off-ball screens on either side, allowing him to run around either for a shot on the breaks.

Hawkins runs around the left screen set by Adama Sanogo, nothing doing. But he then sprints back to the initial under-the-basket spot and decides to hit the other screen – hence, pattern or continuity – running around the Karaban screen on the right side and finding an open shot.

Continuous motion action until boom, open 3.

This is the crux of Dan Hurley’s offense. But UConn is unique because it can slip into other actions when Plan A isn’t in the cards.

Shots haven’t been falling for UConn during this tournament run. The Huskies are a meager 25-for-89 from deep over the past four games, a 28% mark uncharacteristic of a 36% 3-point shooting squad.

So, Hurley has adjusted, leaning into two sets in particular.

First, the Huskies are happy to slip into high pick-and-rolls when the screens aren’t working.

For example, here’s a set from last year’s Big East Tournament semifinal matchup with Marquette:

The Huskies run two stagger screens on each side of the court and find nothing. So, the ball finds its way into Tristen Newton’s hands, who runs a high pick-and-roll with Sanogo before finding Nahiem Alleyne for a corner 3.

This year, Newton and Cam Spencer have developed into buzzsaw ball-screen initiators, with the Huskies trailing only Creighton among Big East squads in pick-and-roll ball-handler PPP (.91).

Meanwhile, Donovan Clingan and Samson Johnson are two of the nation’s elite screen-and-roll men, so the Huskies rank second nationally in roll-man PPP (1.43).

Second, the Huskies use off-ball screens to confuse defenses, allowing big men to slip or duck toward the basket.

My favorite example is from Clingan in last year’s first-round tournament game against Iona:

After a failed right-side stagger screen, Joey Calcaterra and Clingan run a stagger screen on the left side, characteristic of a continuity offense. Karaban runs a twirl action for Calcaterra to come off Clingan’s screen, but the Iona defenders get confused on the switch and sprint toward the 45% 3-point shooter.

So, Clingan cuts toward the rim and finds an easy, uncovered dunk.

Additionally, the Huskies can fail at all actions and simply hit their bail-out option, a post-up set with Clingan. Considering the 7-foot-2 big man generates 1.19 post-up PPP (96th percentile), UConn is happy with this option.

He shredded Coleman Hawkins in the Elite Eight, scoring 13 points on 10 post-up sets, suitable for a ridiculous 1.3 PPP.

With shots not falling, UConn has flowed into more on-ball screen, cut and post-up actions. Instead of scoring 40 points from deep, the Huskies have decided to drop more than 50 paint points in three of their four tournament games.

And that’s why it's impossible to stop Hurley in a one-and-done, short-prep tournament setting. The Huskies can run every action, and they'll find the action that exploits you and attack relentlessly. It's game-plan proof.

This is why UConn has won 10 consecutive NCAA Tournament games by double-digits, and it’s probably why the Huskies will roll to back-to-back championships.

Defense

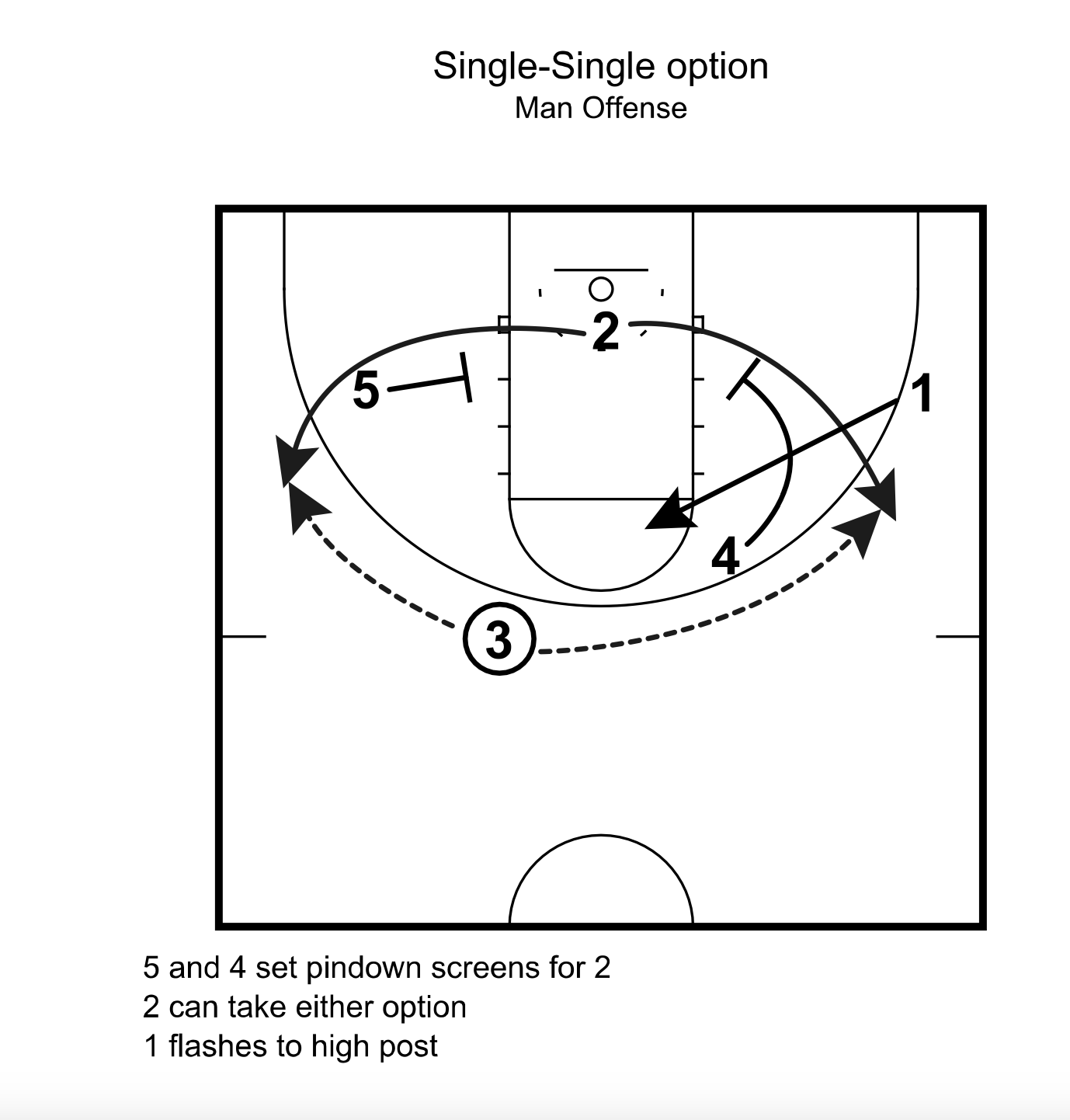

The Huskies run a drop-coverage defense. If you want to learn more about the drop, I highly recommend you read this piece I wrote about Creighton’s KalkDrop in the non-conference.

The basic premise of the drop is that defenders overplay ball-handlers on the perimeter and shooters on the wing, funneling them towards a dominant rim protector who sags into the restricted area. Ultimately, opposing ball-handlers are baited into taking awkward, inefficient mid-range shots.

The Xs and Os are a tad more complex.

Drop defense is primarily a ball-screen coverage defense, where the screener’s defender doesn’t attack the ball-handler on the switch, instead sagging toward a “predetermined drop level” to contain both the ball-handler and roll-man.

The initial on-ball defender forces the ball-handler to use the screen and chases him over the top, preventing a pull-up 3 and funneling him into the middle of the floor.

A key advantage to the drop is it defends ball screens with two guys rather than having to rotate a third defender toward the set, as the whole point of on-ball screens is to generate an advantage in numbers. You sacrifice a mid-range shot but avoid those costly, analytically-friendly open corner 3s or rim-running cutters.

You can see this all cleanly laid out in this Jordan Sperber (Hoop Vision) breakdown:

Running drop coverage is wildly enjoyable when you have a 7-foot-2 monster who blocks 2.5 shots per game, like Cling Kong. Let Spencer, Newton and Karaban run perimeter players off the 3-point line because, trust me, these guys don’t want to attack Clingan – see the Illinois game as an example.

With all this in mind, check out UConn’s statistical profile.

The Huskies rank first nationally in at-the-rim PPP allowed (.94) and top-20 in catch-and-shoot jumpers per game allowed (14). They also rank top-100 in Open 3 Rate Allowed, top-60 in Rim-and-3 Rate Allowed and top-20 in Rim-and-3 PPP Allowed (1.04).

However, I should mention that drop-coverage is the most passive defensive scheme a team can run, as you’re essentially handing opposing ball-handlers the middle of the floor. As such, the scheme forces no turnovers, and elite mid-range creators can shred the drop.

Then again, a passive coverage also means you effectively avoid fouling and foul trouble, which is huge for Clingan.

Purdue in One Line

Edey, the Edeyettes and the No Middle

Offense

The Boilermakers post up at the highest rate in the nation, around 17 times per game.

And why wouldn’t you? The two-time National Player of the Year is an unstoppable force, scoring 182 post-up buckets this year at a 54% clip for 1.05 PPP. He also draws fouls at a stupid rate and cans 71% of his free throws.

There are a few ways to get the ball into Edey in the post, but against single coverage, I’d watch out for Horns High Low, a staple of the Boilermakers' offense.

It’s just a variation of Horns, with some split action for the two bigs at the charity stripe to get that High-Low action.

It's over once Edey gets isolation leverage in the paint.

But Edey’s most significant trait is gravity. You must bring extra help toward him, opening up the perimeter for 3-pointers from Braden Smith, Fletcher Loyer, Lance Jones and Mason Gillis.

Edey is the primary reason Purdue ranks in the top 30 nationally in Open 3 Rate and shot 42% from deep in Big Ten play.

As you can see below, Tennessee's Josiah-Jordan James is stuck trying to help on Edey, thus leaving Loyer wide open at the top of the arc, where he's shooting over 45% this season:

The Boilers have been mainly running with Trey Kaufman-Renn at the four, which helps their ball-screen coverage defense. However, when Painter elects to put Gillis in that spot, Purdue’s spacing and shot-making around Edey becomes almost unstoppable, stretching defensive rotations when teams front the post.

It’s a pretty simple offense: score through the post with Edey or dish it out toward shooters if he gets double (or triple) covered.

Of course, the key difference between last year’s team — which lost to Fairleigh Dickinson in the first round — and this year’s team is that Purdue is a bit more versatile.

Last year’s squad was hyper-dependent on the Edey and the Edeyettes formula. So, if opponents put all their eggs into post-defense and Purdue’s shots don’t fall, things can get 16-seed-beating-a-one-seed ugly.

But the backcourt is a year older, and the Boilers are more comfortable in ball-screens. They’ve significantly upped their pick-and-roll usage, with Smith becoming a key initiator and finisher on those sets.

Here’s a nice high ball screen with Smith and Edey, where Smith finishes it off with a floater:

If defenses put all their resources into defending Edey in the post and the shots aren’t falling, the Boilermakers have a third, viable option.

That really came to light against Tennessee, where the Boilers shot 3-for-15 (20%) from deep but scored 21 points on 22 ball-screen sets (.96 PPP).

Ultimately, however, the offense is mostly Edey hitting turnaround hook shots or drop-step dunks, getting fouled or dishing it out to perimeter shooters. The ball-screen buckets are just a bonus.

Defense

Purdue’s defense has changed drastically throughout the year.

The Boilers used to run drop-coverage concepts with Edey, but they’ve moved to a more hard-hedge ball-screen coverage, while deploying no-middle concepts on the interior.

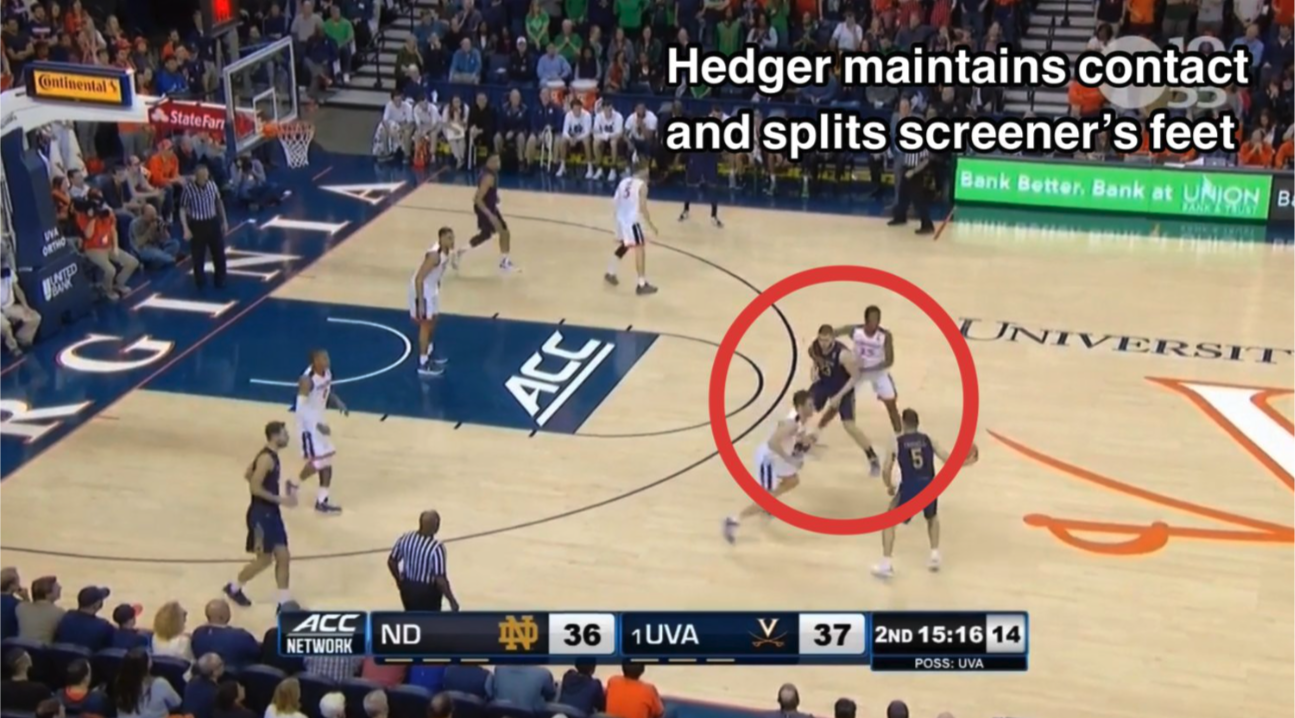

Hard hedging involves, as Hooper University puts it, “the screener’s defender getting parallel to the sideline behind the screener, and aggressively sliding high as the ball handler comes off the screen to slow him down and force him to retreat towards the half-court.”

It’s an on-the-level ball-screen coverage defense that prevents the ball-handler from driving downhill.

No-middle concepts are much more interesting to explore, something I did a few years ago by analyzing Scott Drew’s Baylor team that won the 2021 title.

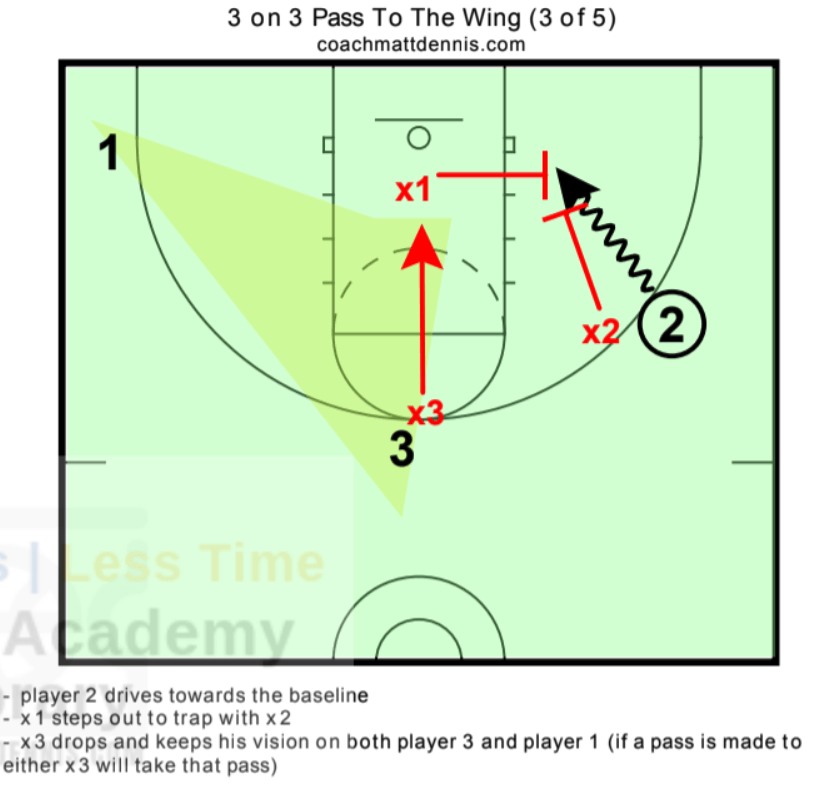

While Drew’s defenses are predicated on no-middle concepts at the point of attack, Purdue uses those concepts in the restricted area. And down there, the no-middle emphasizes bringing extra-and-early help across the baseline toward driving attackers, trapping them before they get into the paint while using the sideline and baseline as an extra defender.

Meanwhile, the weak-side defenders zone up, looking to pick off cross-court passes.

Specifically, Purdue will sometimes bring Kaufman-Renn and Gillis across the baseline as the early/extra helper, generally putting them as the leading defender in front of the rim-protecting Edey. Thus, the Canadian big man avoids on-ball fouls and foul trouble.

Ultimately, however, Purdue’s defense is nothing special, primarily because of Edey.

As mentioned, Kaufman-Renn's buzzsaw ability keeps the Boilermakers’ ball-screen coverage defense afloat. However, the Boilermakers really struggle to stop secondary actions like DHOs (1.02 PPP allowed, 20th percentile) and off-ball screens (.91 PPP allowed, 28th percentile).

And that’s because Painter has no idea what to do with Edey as a middle-of-the-floor defender. If you can get the 7-foot-4, laterally slow Boilermaker in space and out of position, you can attack and score on him.

Gonzaga did that brilliantly – at least in the first half before getting into foul trouble. The Bulldogs ran plenty of DHO continuity sets that dragged Edey away from the precious paint and carved him up, scoring 15 points on 10 secondary actions (1.5 PPP).

The good news is that Edey is a solid post-up defender, and Kaufman-Renn is elite. But things can get dicey if the Boilermakers' bigs get moved around.

Alabama in One Line

Oats Ball, Baby

Offense

Sometime mid-season, Nate Oats leaned entirely into small-ball creation with Rylan Griffen at the four.

And the Crimson Tide have become impossible to stop — a true tidal wave of points.

Oats-ball is the most analytically friendly form of basketball. You attack the rim or shoot a 3, avoiding mid-range buckets at all costs.

Bama primarily pushes the floor and uses quick-strike DHO, ball-screen and slice actions to drive, shrink the floor, draw the defense down and then kick the ball out for a 3 if the layup isn’t there.

Here’s an excellent example of a quick-strike, high ball screen into an off-the-dribble 3 from the ever-versatile Griffen:

The Tide's offensive versatility is what makes them so deadly. Mark Sears can dribble, penetrate or create from any ball-screen set. Aaron Estrada and Griffen are deadly, popping around off-ball screens and into space. Grant Nelson is a mismatch nightmare for any frontcourt defender with his post-up and floor-stretching ability — plus he’s lethal in transition.

They’re all great on-ball drivers, great shooters and mismatch nightmares. So, the Tide can run their actions, drive the lane, beat their man or kick it out to another spot-up guy who will make the 3, drive the lane, beat their man or kick it out to another lethal shooter, et cetera ad infinitum.

Here's a tremendous example of the Tide shrinking the floor with two drive-and-kicks, first from Sears to Estrada and then from Estrada to Jarin Stevenson:

It’s barbecue chicken once Clemson's Joe Girard III comes down to help on Estrada.

And the Tide's lethal small-ball lineup gives them floor-spacing and shot-making ability unparalleled at the collegiate level, where the Tide rank fourth in ShotQuality’s Spacing metric, fourth in their Shot Selection metric and 31st in their Shot Making metric.

They also rank third nationally in Rim-and-3 Rate, but that goes without saying.

Oats-ball, baby.

I’d like to think that a great rim-and-3 and transition defense can stop the Tide, but that hasn’t been the case so far. Clemson and North Carolina are great at both, and the Tide obliterated them for 89 points in each matchup.

Of course, Alabama shot 27-for-62 (44%) from deep across the two matchups, and that level of shot-making is unsustainable for any offense.

But the 3s will always come for Alabama — the Tide are shooting 37% from deep on the year — and they can come in droves. If Bama’s 3s are falling, the Tide can roll anyone, especially if Sears gets hot.

Defense

Oats sacrificed any rim protection or rebounding when he made the aforementioned small-ball move.

Bama runs a drop-coverage defense – a la UConn – and the Tide used to run it effectively with Charles Bediako as the anchor. But Nelson is a horrific interior defender (1.00 post-up PPP allowed, 33rd percentile), and Griffen is 6-foot-7, so opposing frontcourts and rim-runners have destroyed them.

Meanwhile, Sears, Estrada and Griffen are turnstiles as point-of-attack, ball-screen coverage defenders, meaning opposing offenses can dribble-create freely into the middle of the floor and then toward the rim.

And, again, nobody rebounds. The frontcourt is too small and too slim.

A drop-coverage defense with zero rim protection or effective perimeter over-the-top chasers is a recipe for disaster. And, as mentioned, the drop doesn't force turnovers, which doesn’t help Alabama’s transition-friendly offense.

As such, Alabama ranks sub-100th nationally in Defensive Efficiency, sub-290th in defensive turnover rate, sub-270th in defensive rebounding rate, sub-190th in 2-point shooting allowed, sub-270th in paint points per game allowed and sub-330th in second-chance points per game allowed.

Diving deeper, Alabama ranks below the 30th percentile of D-I teams in post-up PPP allowed, ball-screen PPP allowed, cutting PPP allowed and at-the-rim PPP allowed.

Even worse, the Tide are poor isolation defenders (.87 PPP allowed, 23rd percentile) who foul far too often (311th in free-throw rate allowed), two things that the drop-coverage scheme should avoid.

It’s a disaster all around. Alabama is entirely reliant on out-scoring the opposition.

Oats ball, baby.

NC State in A Line

Burns, Baby, Burns

Offense

It’s all about DJ Burns Jr.

He’s too large and physical. His footwork is too good. His bag is deep.

The combination is too much for any one-on-one defender to stop.

Burns obliterated Kyle Filipowski in the Elite Eight, forcing him to foul out, and then dog-walked Ryan Young after. He finished the night scoring 18 points on 13 post-up sets, suitable for a whopping 1.4 PPP.

He also scored 11 points on 10 post-up sets (1.1 PPP) against Oakland and 14 on 16 (.88) against Texas Tech.

But if you bring extra help, trying to trap him or front the post, his vision and passing ability will slice and dice any weak-side defense. Marquette tried to do that, limiting him to only four shots, but he went ahead and dished out seven assists.

As a result, NC State posts up at a similarly high rate to Purdue, the 12th-highest rate in the nation.

And why wouldn’t you when you have this guy:

But while Purdue leverages its big man to open up perimeter shooters, NC State tries to open up the middle-of-the-floor secondary actions for stud point guard DJ Horne.

Horne is a shot-creating wizard, and he’s money once he finds an isolation mismatch out in space (1.07 iso PPP, 86th percentile) or gets a decent spot-up opportunity (1.29 spot-up PPP, 97th percentile).

As such, the Wolfpack generate long mid-range opportunities at a top-30 rate (16% of the time). It’s not analytically friendly, but it works because they force mismatches across the half-court – you can’t stop Burns in the post, and you won’t stop everyone else when doubling and defending man-down.

It’s also worth mentioning that NC State is an excellent rim-running cutting offense (1.29 PPP, 85th percentile), which is obvious when Burns is dishing to cutters from the high post.

This is the absolute best example of the Wolfpack's DJ-to-DJ offense:

Marquette tries to trap Burns near the left block, but as Kam Jones leaves Horne as he rotates toward Michael O'Connell toward the left break, that allows Horne to cut freely into the middle of the paint, where Burns will always find him.

I just wish the Pack cut more, as they’re only in the 31st percentile regarding cutting frequency.

Defense

Similar to Purdue and Edey, Burns’ complete lack of lateral mobility is a liability on defense.

That's specifically the case in ball-screen coverage, where the Wolfpack can’t stop a nosebleed.

The Pack rank 274th nationally in pick-and-roll points per game allowed (10). They hung tough against Marquette and Duke but allowed Texas Tech and Oakland to score 47 points on 44 combined ball-screen sets, suitable for 1.07 PPP.

Because if you put Burns into a ball screen and force him to move into space and out of position, he won’t be able to move or keep up with anyone attacking him.

Similarly, the Pack struggle with Burns when defending against middle-of-the-floor secondary actions, just as Purdue does with Edey.

Coach Kevin Keatts has switched up his defense a bit during this tournament run, scaling back press coverage and opting for one-on-one post-defense while switching everything on the perimeter to deny perimeter shots.

Specifically, he’s cross-matched Burns in post-coverage, letting Mo Diarra or Ben Middlebrooks handle the more prominent post-up threat while hiding Burns on the other big man. Like Purdue’s no-middle strategy, it helps keep Burns out of foul trouble.

Burns is surprisingly OK when defending post-up sets one-on-one (.79 PPP allowed, 64th percentile), but opponents would rather move him around than attack him directly.

I’d like to think the perimeter switching has helped with NC State’s 3-point defense, as opponents have shot 28% from deep since the start of the ACC Tournament – or the beginning of the Pack’s miracle run.

But I also think that’s just general variance luck. That’s fine. Every team needs a Four Leaf Clover to make a Final Four run (unless you’re UConn).

I’ll be curious to see if all that looming regression hits NC State in the Final Four, especially if the Pack are still cross-matching Burns in post-up coverage while Purdue has Gillis at the four, which will put plenty of stress on their rotations.

NC State is dependent on Burns, for better or for worse. Hence, either Burns is so good, or Burns is so bad.