On July 1, college athletes are going to be able to capitalize financially on their name, image and likeness.

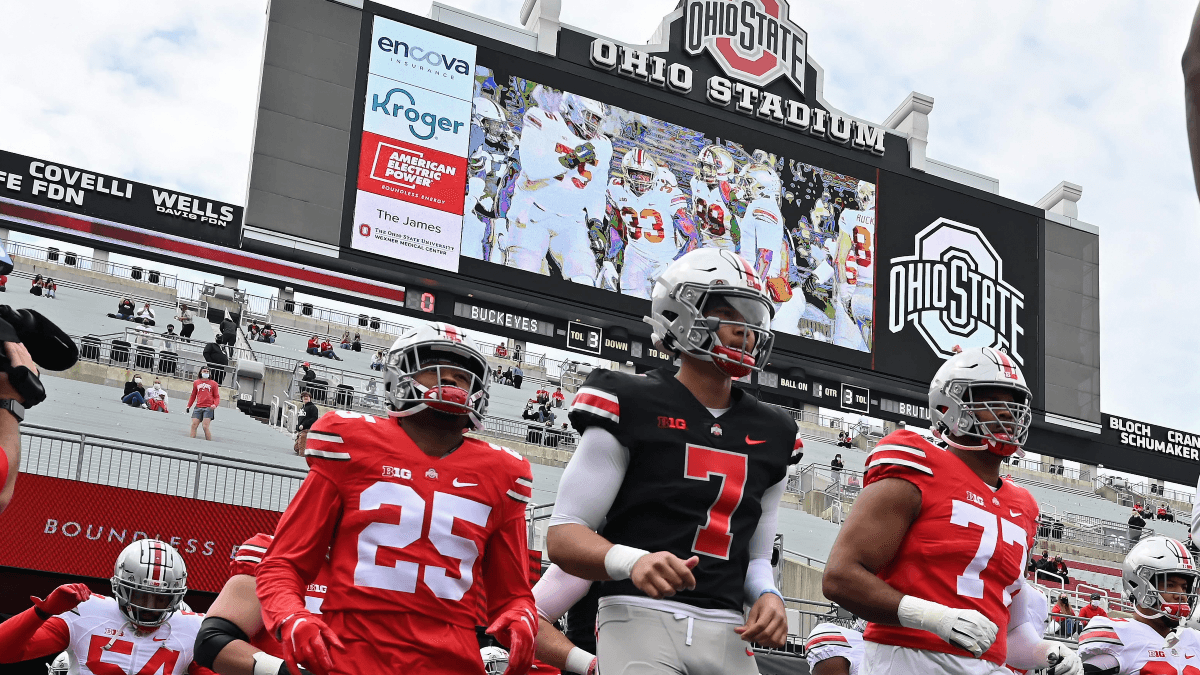

Eight states — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Ohio, New Mexico and Texas— have laws that will go into affect right away, with other states on the way. Schools with states that haven’t passed any laws will be left up to their own devices, which will surely keep compliance departments busy.

To make sense of it, we sat down with Darren Heitner of Heitner Legal, a law firm that aided the Florida legislation and has consulted with athletes, schools and companies on the matter.

Rovell: For outsiders, it seems like this could be the Wild, Wild West.

Heitner: Well, given the recent court decision, I think the NCAA is going to be very careful to put any meaningful restrictions on what can be done. That being said, there are still rules and it will be left up to the universities to enforce those rules.

Rovell: We know athletes can do social media, appearances and billboards. Can a high-profile football player sign a shoe deal that conflicts with the university’s deal?

Heitner: In most states, including Florida, there’s guidance that these deals that athletes are signing can’t conflict with the school’s third-party deals. So Florida, for example, has the Jordan brand. I don’t think an athlete can play a game in Adidas because that could constitute breach of contract.

However, that doesn’t mean the best player on the team can’t do an Adidas deal. It would just have to be off the field or court. They could create ads and take pictures and pose in their dorm room.

Rovell: I wrote my first article on athletes capitalizing in 2002 and it was in reference to jersey sales, where athletes would get a cut of the sales of jerseys with their name on the back. It doesn’t seem like that will be part of this, at least initially.

Heitner: I think the thinking is that if that happens soon, schools are creating a business relationship with the athletes and they are reluctant to do that.

Rovell: One of the rules is that athletes can’t participate in anything that has the trademarks of their school, but they can use colors. Should they be concerned down the road of using specific colors that match their team?

Heitner: I don’t think color is going to become an issue. I’m not sure it’s protectable, and with everything going on I frankly don’t think it’s worth fighting for.

Rovell: At first, it was assumed the states that have the laws in place were going to have the advantage because athletes in schools in those states could capitalize. Now, it looks like athletes in all states can capitalize, so doesn’t the advantage lie in a state that has less strict rules?

Heitner: I don’t think that’s clear. I don’t believe schools in states without laws will necessarily have much lesser restrictive policies.

Rovell: USC proudly made logos for their basketball players. Are we going to see schools try to get players by saying, “Being at our school is better business”?

Heitner: I think schools in states that already have laws have to be very cautious about helping athletes procure business. If schools help athletes find deals, I think they open themselves up for huge exposure if something goes wrong.

Rovell: What are the first type of deals that get signed?

Heitner: You are going to see camps, clinics, personal appearances, autograph signings, memorabilia and NFTs.

Rovell: Where is the advantage in recruiting in the name, image and likeness era.

Heitner: Schools that have advantages will still have advantages, but I think schools that are more powerful in their respective sports in larger markets could have a greater advantage.

Rovell: What can’t athletes do?

Heitner: Well, it depends on what state you are in — and if there are no laws, on your compliance department. I can tell you that Texas and Ohio have very specific language about not allowing casino, sports betting and adult entertainment.