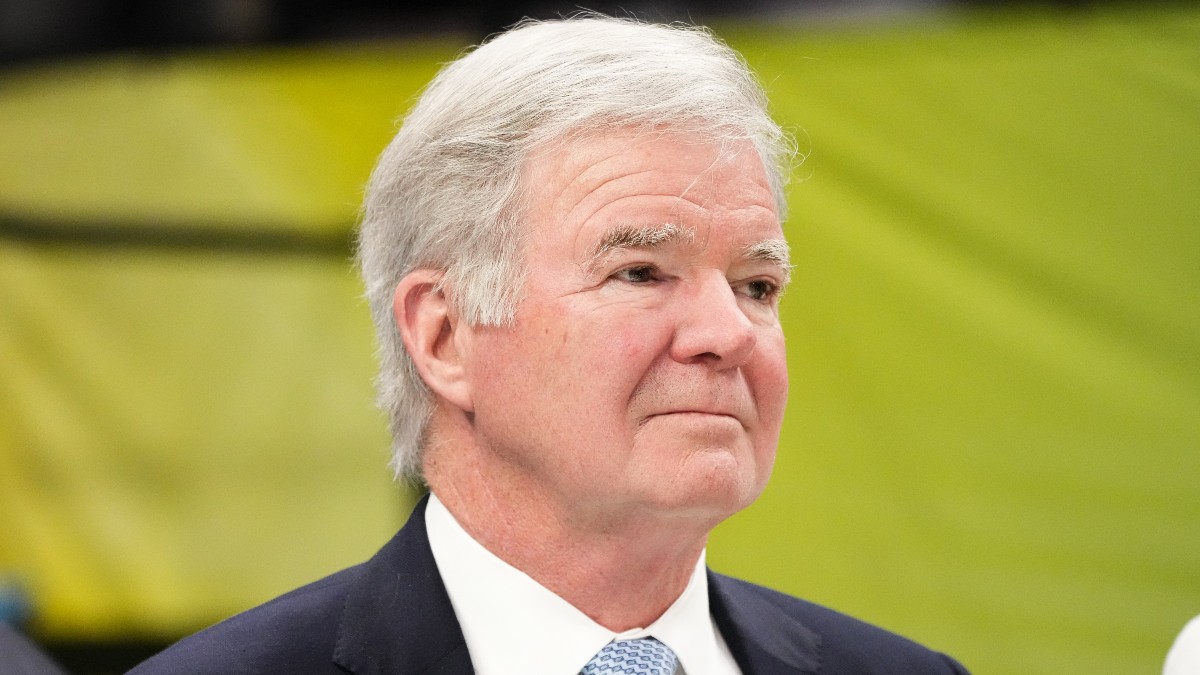

Today is Mark Emmert's last day as president of the NCAA.

Not many people are tuned into that fact because his job doesn't matter anymore. And neither does the NCAA.

The bulk of that onus falls on Mark Emmert's lap — and the board that allowed him to do what he did.

Or alternatively, not do anything.

When former president Myles Brand died in 2009, it was very clear that the next NCAA president had to actually do something. Prior to this, the job of the NCAA president was to be a philosophizer. Talk around and around topics and do what you have to do to keep athletes from earning a dollar.

Brand, for example, was able to get away with saying for years that he was "looking into" athletes getting paid for the name on the back of their jerseys. It was clear that Emmert was going to have to bridge the gap between student-athlete and emerging revenue streams, including video games.

He blindly ignored the blatant use of athletes' unique and unmistakable characteristics in these games, leaving the organization exposed. The athletes rightfully won their long-fought case, awarding them compensatory fees and leaving the NCAA under a falling sword.

Had Emmert had a semblance of foresight, he could have read the writing on the wall and proceeded to facilitate the payment of players, serving as an intermediary between member institutions.

Instead, he failed entirely.

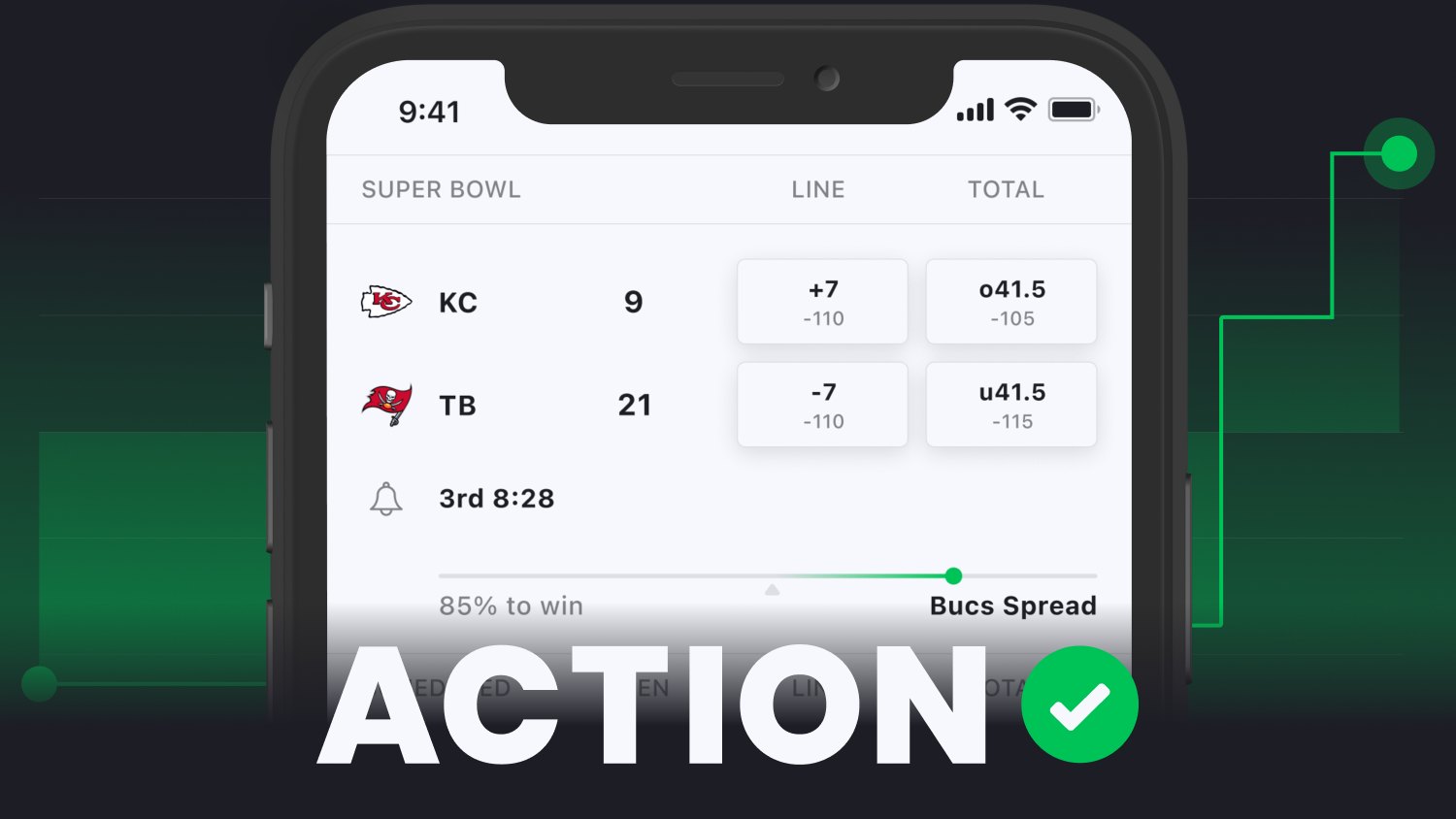

When the NCAA is not around in 2033, everyone will look back on July 1, 2021 as its death knell, when name, image and likeness was implemented.

With the NCAA not showing any progress toward fairly compensating their talent — or allowing them to do endorsement deals — the Supreme Court stepped in and forced the NCAA's hand.

The NCAA was now nothing. They couldn't control compensation over name, image and likeness and they could no longer enforce any of these deals.

Their last ditch efforts to consolidate power were almost as sad as their preventative efforts.

The NCAA argued that deals from collectives couldn't be inducements for players to join schools. But schools have an arm's length distance from such collectives, meaning the NCAA has little to no power to do anything.

A week ago, the NCAA levied its first post-NIL violation centered on the University of Miami. The violation? A dinner for the Cavinder twins, who eventually went to the school. And I thought we were long past the days where the NCAA was worried about offering athletes extra cream cheese on a bagel.

Mark Emmert was paid $29 million for his services over the last 12.25 years. Sure, there's a replacement coming in Charlie Baker, but the NCAA won't be around for anyone to come in after him.

In not getting with the times, the NCAA made itself irrelevant, reducing itself to a glorified event company that puts on championships. For a couple million, current NCAA members can hire a production company to do what the NCAA does and eliminate the organization forever — all thanks to Emmert.