Michael Pratt’s mother, Rori, had a project for her son, who just happens to be Tulane’s starting quarterback. A research project to be precise.

She was worried about the short- and long-term impact of head injuries suffered in football after her son was leveled by a vicious hit last season against SMU, resulting in concussion-like symptoms.

“After last year, my mom was a little concerned with concussions,” Pratt said. “So, she told me to research it and see what I could find out.”

Pratt spent a few weeks reading and researching everything related to concussions. Pratt discovered that former Carolina Panthers linebacker Luke Kuechly had missed nine games in a two-year span because of concussions but remarkably missed only one game the following three years simply because he started wearing an experimental collar device on his neck.

“When I read that, I was encouraged and reached out,” Pratt said. “I wanted to protect myself.”

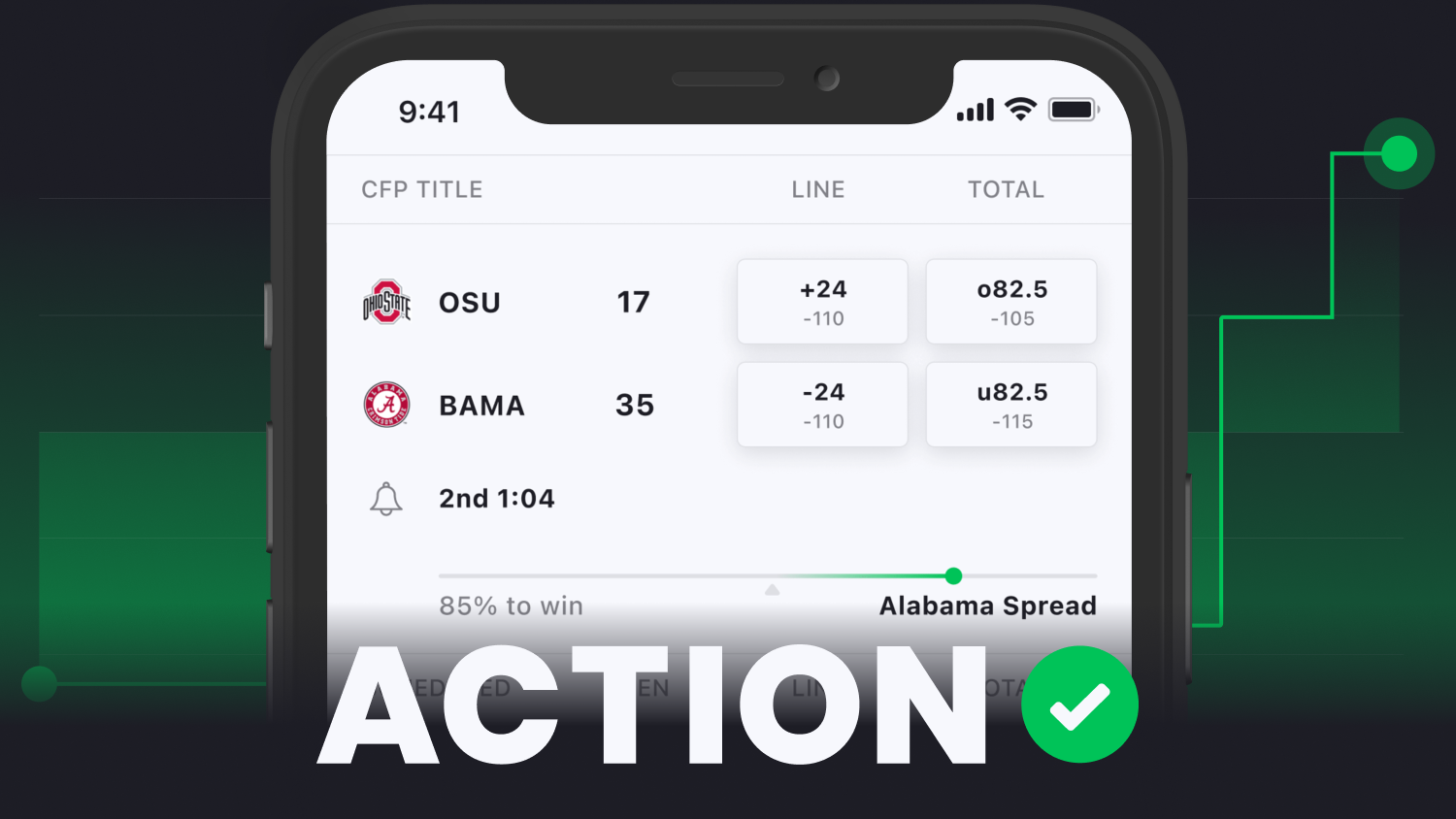

That experimental device — the Q-Collar — is no longer an experimental device. In 2021, the Q-Collar, produced by Q30, received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It is now worn by more than 20 active NFL players, including Panthers linebacker Shaq Thompson, Cowboys running back Tony Pollard and Chargers linebacker Drue Tranquill.

Pratt is among more than a dozen college players wearing it. Programs including Alabama, Arizona, Baylor, Delaware, Michigan State and SMU have all purchased the Q-Collar for players on their respective teams.

“My head has felt pretty good throughout the year,” Pratt said. “The collar reduces movement of your brain inside your head and helps avoid concussion. Whether I’ve just been lucky or it’s because of (the collar), I’m going to keep wearing it.”

There’s been nothing lucky about Pratt’s Tulane Green Wave. Behind Pratt, Tulane (7-1) is ranked No. 23 in this week’s Associated Press Poll and last week cracked the AP rankings for the first time in 24 years. Not bad, especially after Tulane’s 2-10 season in 2021.

“Everything is paying off for us,” Pratt said. “A lot of guys have stepped up. Seeing our vision play out has been really cool. It’s an awesome feeling.”

How Does the Q-Collar Work?

The band, which is made with similar material as a Fitbit, wraps around the back of the neck and places about 1.2 pounds of pressure on the internal jugular vein, which carries oxygen-free blood from the brain back to the heart.

This increases the blood volume in the skull, providing extra cushion and an airbag effect for the brain against the skull during any impact against or to the head.

“Just putting a little bit of a kink in the hose of the jugular vein or collar is enough to place a teaspoon or two (more blood) in the brain, and that seems to be sort of like bubble wrap or it limits the brain’s ability to move,” said Julian Bailes, Chief Medical Advisor for Q30.

The Q-Collar received FDA approval after the organization assessed the safety and effectiveness of the Q-Collar through several studies. One study featured 284 teenage high school football players. The study found “no significant changes” in deeper tissues of the brain in 77% of the players who wore the Q-Collar compared with only 27% that didn’t wear it.

“Think of the Q-Collar like a seatbelt for your brain,” said Suzanne Williams, Q30’s vice president of sports marketing. “You put your seatbelt on, and it keeps you from moving in your car if there's an accident. It’s not 100%, but it helps you a lot of times. That’s the main focus.”

Dr. David Smith, the co-inventor of the Q-Collar, initially got the idea from nature, specifically the woodpecker and ram. Smith spent nearly a year researching why — despite repetitive blows to the head area — the woodpecker and ram were rarely fazed or stunned.

Smith discovered they had internal devices that modulated and changed the pressure and volume inside the cranial space, which prevented concussion symptoms.

And the Q-Collar was born.

|

Photo Credit: Q30

Washington Commanders running back JD McKissic said wearing the collar was something “I had to do. We love football. We love to see the guys play, but at the end of the day, you want to be protected. I'm taking measures to protect my brain. You’ve got to take care of yourself at the end of the day.

“When you talk about the brain, you only get one brain. So, if you can find any way to protect yourself on the field, you do it.”

While Pratt found out about the Q-Collar through his own research, Texas’ top athletic medical officials recommended the device to UT linebacker DeMarvion Overshown after he suffered a concussion last year.

Allen Hardin, UT’s senior associate athletic director and chief medical officer, and Donald Nguyen, UT’s senior associate athletic trainer, had witnessed firsthand how the Q-Collar worked for Audrey Warren, a forward on the Longhorns’ women’s basketball team.

As a freshman, Warren, who had a knack for taking charges, had suffered four concussions. She had several concussion-related issues until she started wearing the Q-Collar.

“I wanted to be able to play and not risk my health,” Overshown said. “They suggested I give it a try. It’s been unbelievable. Not only being safe but going out there with confidence. I don’t have to worry about that. That’s huge playing the sport we play. Confidence is everything.”

Pratt said he has noticed a difference in how it makes him feel on the field.

“Anytime you have an injury or an issue, you don’t want to have the injury again,” Pratt said. "You have to be 100% mentally locked in, and this gives you a great sense of confidence.”

Both Pratt and Overshown said the first time they wore the Q-Collar, it felt snug around the neck. They both said by the third day, they had forgotten they had it on. Besides wearing it in games, both players said they wear it during all contact practices.

“I’ve had a couple of hits this year, that I felt if I had those last year, I would have been out of the game,” Overshown said. “With the Q-Collar, I was really able to get back up. I didn’t feel funny. One of those hits was where everyone wonders immediately ‘Is he OK? Is he going to be carted off?’ And then I bounce back up. I just feel normal after these major hits.”

|

Photo Credit: John Rivera/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images.

Williams said Q30 doesn't pay athletes to wear the Q-Collar, although the company does have NIL deals with Pratt and Overshown. A collar costs $200 and comes in various sizes, which are custom fitted.

“This is a game changer,” Overshown said. “It’s not going to be mandatory, but players will want to wear it when they hear about it. They don’t have to miss any playing time knowing they’re protected.”

Pratt also believes the Q-Collar will be a regular piece of equipment, like shoulder pads or a helmet.

“I wouldn’t doubt it,” Pratt said. “I don’t see why you wouldn’t wear it. I could see it being something everyone is eventually wearing one day.”

And when that happens, Overshown figures he’ll stop getting asked what exactly he’s wearing around his neck. Earlier this season, a Texas assistant asked Overshown what he was listening to at practice.

The coach thought the Q-Collar was a Bluetooth device. Others have thought it was a motorized fan.

“I like to tell people they’re my dog collars,” Overshown said, laughing. “They only give them to dogs on the team.”