You don't really ever wake up thinking, "OK, today I'm going to that work event, I need to pay the power bill and oh, if I have time, I'll debate the value of data through the prism of the mid-range with an NBA future Hall-of-Famer."

And yet, here we are.

Tuesday morning, drinking my morning Red Bull (don't judge me, only God can judge me) I decided to zip into the conversation held on ESPN's "The Jump" about Zach LaVine and the value of mid-range jumpers in the modern NBA.

OK I’m up for this today.

-Rachel mentions it’s a good shot if it goes in and a bad shot and it doesn’t. But YOU DON’T KNOW IF IT WILL OR NOT BEFORE YOU SHOOT.

Zach LaVine shot 35.8% on mid-range shots last year. That’s not analytics, that’s a math fact. He shot 37% on 3’s! https://t.co/OjquwWkQ29

— Hardwood Paroxysm (@HPbasketball) October 15, 2019

Spoiler alert: I was not up for it, at least for how it evolved. It should be noted that the original article involving LaVine's approach to analytics and the mid-range was not well received by LaVine.

I see we're making Zach LaVine and mid-rangers a topic today.

Perhaps important to note that Zach wasn't a fan of the article that started everything? pic.twitter.com/octrX6TkS7

— Morten Stig Jensen (@msjnba) October 15, 2019

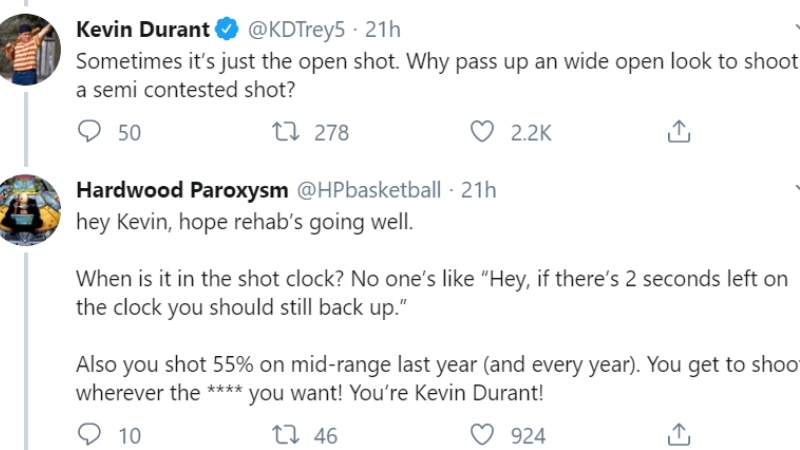

So anyway, I was just looking to wax a little on the difficulty of how much players trust their mid-range vs. the cold hard facts of how often those shots are converted … when a notification popped up:

Sometimes it’s just the open shot. Why pass up an wide open look to shoot a semi contested shot?

— Kevin Durant (@KDTrey5) October 15, 2019

And so began a very strange day.

This conversation with Durant carried on, surprisingly, over a series of tweets over the next few hours. Durant responded to others who popped in as well, including this moment, which has 12,000 likes and generated some content for all the aggregators.

Who the fuck wants to look at graphs while having a hoop convo?

— Kevin Durant (@KDTrey5) October 15, 2019

I have to stress this: Durant opted to respond to a tweet of mine, but he wasn't just talking to me — he was just hanging out on Twitter. He's done it before; he'll do it again. He responds to all manner of people. He follows 1,400 people.

Presumably, most of them don't use graphs to talk about basketball.

But while getting digitally dunked on was amusing, this was the most interesting thing Durant said:

I don’t view the game as math. That’s the only difference in the convo. I get what you’re saying but we just have 2 different views of the game. Analytics is a good way to simplify things tho.

— Kevin Durant (@KDTrey5) October 15, 2019

This is a fundamental disconnect with most players and media, and, honestly, most fans. Players don't experience the game as something they observe — it's something they do. It is in itself an experience, and their frame of reference for it isn't based on what they've seen or the box score but by how it felt to play.

I asked Nikola Jokic last year how much he pays attention to the scouting report, and he said not much in the regular season, on account of his familiarity with most of the players. He knows which guys will shade him to the baseline in the post, which will play him tight at the elbow. He's able to draw from experience.

The problem with this, of course, is that memory and the human experience is faulty as a reliable narrator. You remember things that, when you go back and actually watch on camera, didn't happen. This ties back in with the mid-range discussion: Players will say, "I know I can hit that shot."

That may be perfectly true — the player feels he can. Except that doesn't actually matter if he doesn't, you know, actually hit them. It doesn't matter if a 40% mid-range jumpshooter (league average) feels he can knock down that open mid-range jumper if he does it a rate in which other shots would create a better outcome for the team.

There's context needed in all this: what's the shot clock, who's the shooter, is it open or uncontested? But the core question is whether a player knows more than what the numbers, which objectively state what has happened with all players over the past 30 years, tell us.

This isn't to say that numbers are reliable narrators. They're often not. Judging Durant off a night in which he shot 4-of-18 ignores the level of difficulty on those shots and the necessity of those shots in bending the defense and creating the kinds of looks his team wants.

The numbers aren't an end-all. But the misnomer is that there are all these analytic supporters who feel they are. In reality, that slice of basketball fandom is very small.

Another big part of this has to do with where a player fits inside a team construct.

I think every 1st and 2nd option in the nba should ignore analytics n just hoop off feel. Most of them do.

— Kevin Durant (@KDTrey5) October 15, 2019

Durant's obviously different in this case, though. He is literally in the top 95th percentile or better than every human being who has ever played basketball. He's great at the mid-range (55%), he's great from 3-point range and he's great at the rim and with a fox and in a box and in the lane and on a plane.

The same is true of Kawhi Leonard, LeBron James and Steph Curry — the best players in the league. What often separates superstar players is precisely their ability to convert low-percentage opportunities at a high rate, effectively punishing the defense for what it allows.

This is a big sentiment in the conversation: Take what the defense gives you. If they aren't going to guard your mid-range, shoot it.

Except… why exactly is an NBA-quality defense just giving you that shot? No team is giving Durant the mid-range, because any scenario in which Durant shoots is worse than any other option. (Well, now that he's not teammates with Steph Curry and Klay Thompson, anyway.)

The defense gives you a shot because they are aware at some level (player, coach) that you are not good at making more than you miss (or that it's preferable to another shot).

But getting back to Durant's idea of first or second options: Sometimes players are in that position by default. Andrew Wiggins is a first or second option, and he wound up taking 4.4 shots from the mid-range last season, making just 34.7%.

This is not a complicated formula. I'm not calculating Win Shares or tweaking Real Plus-Minus here. This is just: for every 100 shots Wiggins took, he shot 27 from mid-range, and of those 27 he made roughly 9. That's 18 possessions for every 100 he himself used on a shot that resulted in zero points.

Imagine watching a guy come up empty on 18 possessions.

No one's expecting him to make 20 of the 27. No one's even expecting him to make 15 (Durant's conversion rate on such shots). But Wiggins also shot 33.9% on 3-point shots — just one percentage point lower, with the extra value of another point.

But again, those are numbers. And numbers aren't feelings.

The point here is not to bag on Wiggins; there's no shortage of that lately. It's just to illustrate that if Wiggins were shooting 55% like Durant does on those shots, no one would criticize those shots. If LaVine shot 55% like Durant does, no one would criticize those shots.

Durant mentioned early in our "conversation" that the only way to be able to make those shots is to take them. He's not wrong: players will consistently tell you that in-game experience for shots is the only way to improve them. Practice just isn't the same. (Just look at how most bad-free-throw-shooting big men shoot free throws in practice vs. in a game.)

So then the question is: At what point should a player try to optimize the things he's definably good at vs. trying to develop areas he struggles in? That's a whole other complicated question, but it's at the heart of the matter. Should you do what you're good at or do what you might be capable of?

I'm empathetic towards Durant, who is basically like a winged man trying to explain the complexities of flight to a boulder-person or someone physically rooted to the ground. Analysts like myself rely on data, along with players' and coaches' insight and rigorous repetition in watching clips, to try and close that experiential gap.

There is a line of thought that basically says this argument can't occur. Durant knows more about the game of basketball than I do. That's not argument; that's a fact. I can't tell Kevin Durant what a good shot is (nor would I ever try to).

But let's say we lower the bar. Let's take it from Durant to B-level star. Or starter-caliber. Or reserve. Or end-of-the-bench guy. Those guys are all going to have more experiential feel for the NBA because they've played in it.

Now, if that's the approach you want to take, that's fine, but it 1) limits the conversation to very few people and 2) reduces the conversations around the game to base, subjective discussions.

"They played good."'

"Yup, they sure did."

"The other team played bad."

"Yeah, they lost for sure."

Who wants that to be the way we talk about basketball? That's worse than graphs!

I have to rely on data because I can't describe to you what the difficulties are in getting off a crossover pull-up jumper with 5 on the clock vs. the outstretched arms of Jrue Holiday.

I can at once freely admit Durant's superior perspective while also simultaneously holding value on empirical evidence.

The best analogy I've found is a forest. Durant can tell you what that hill feels like to walk up, about that sneaky switchback the river takes in the gulch, about that rattlesnake den on the blind corner.

But the data tells me how many trees are in the forest, traffic patterns in and around the forest, the temperature, any fire warnings or other dangers. All of the information is useful. The question is: How do you bridge the gap so you can see both the forest and the trees?

Or, I guess more accurately, do you need to know the data about the forest when you're walking through it?

And do you need to know how the wind feels in the morning when you're trying to make policy changes to it?

This is the gap we learned more about from Durant on Tuesday.